Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – East Bakersfield

Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods – Public Housing

Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

The Two Chinatowns of Bakersfield

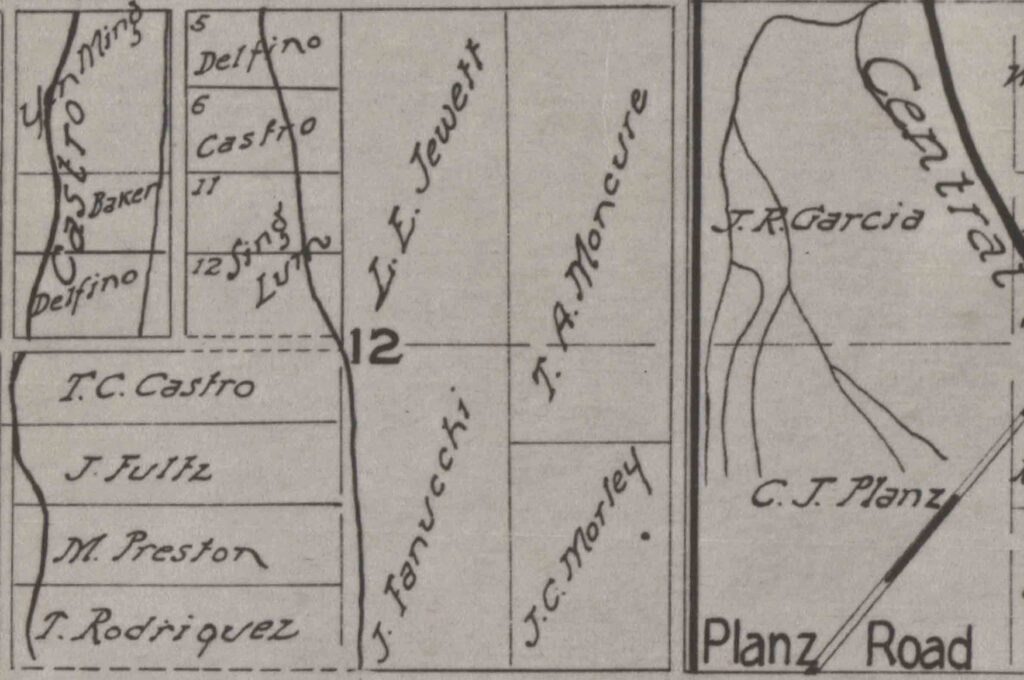

Any survey of a Bakersfield map quickly reveals the long-established presence of Chinese immigrants and their descendants in the city’s street names, ranging from Ming Avenue in the South to China Grade Loop in the North.

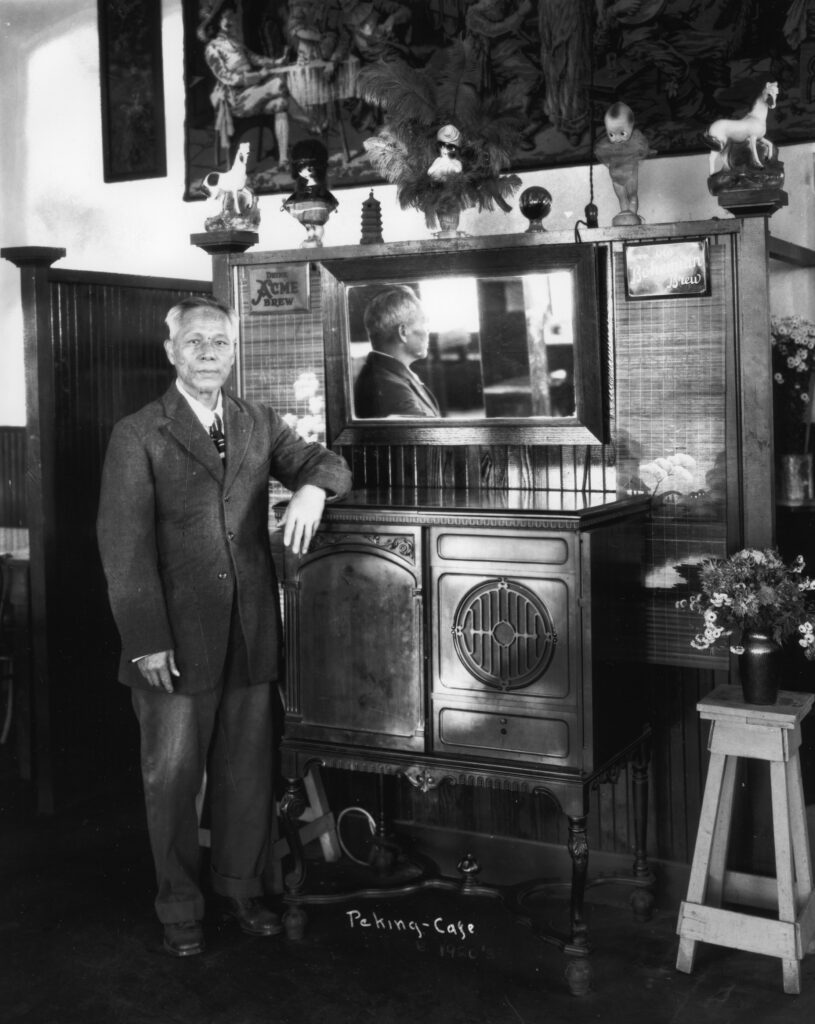

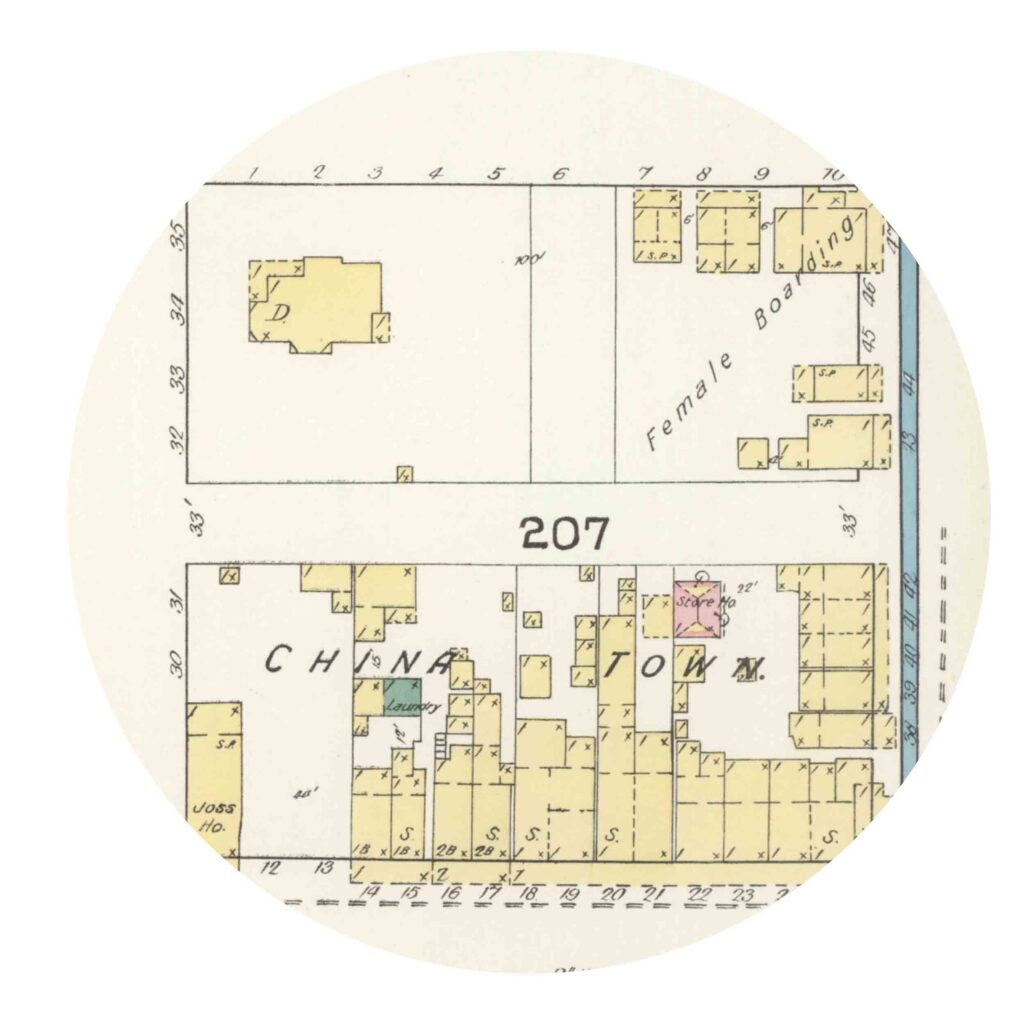

Yet one of the most easily overlooked keys to this rich history lies within a single block: tucked between L and M Streets downtown and located immediately behind the KGET television station on 22nd Street, is a small street colloquially known as China Alley. Along with the adjacent Ying On Fraternal Hall, this alley now stands as the only remnant of Bakersfield’s once-bustling twin Chinatowns.

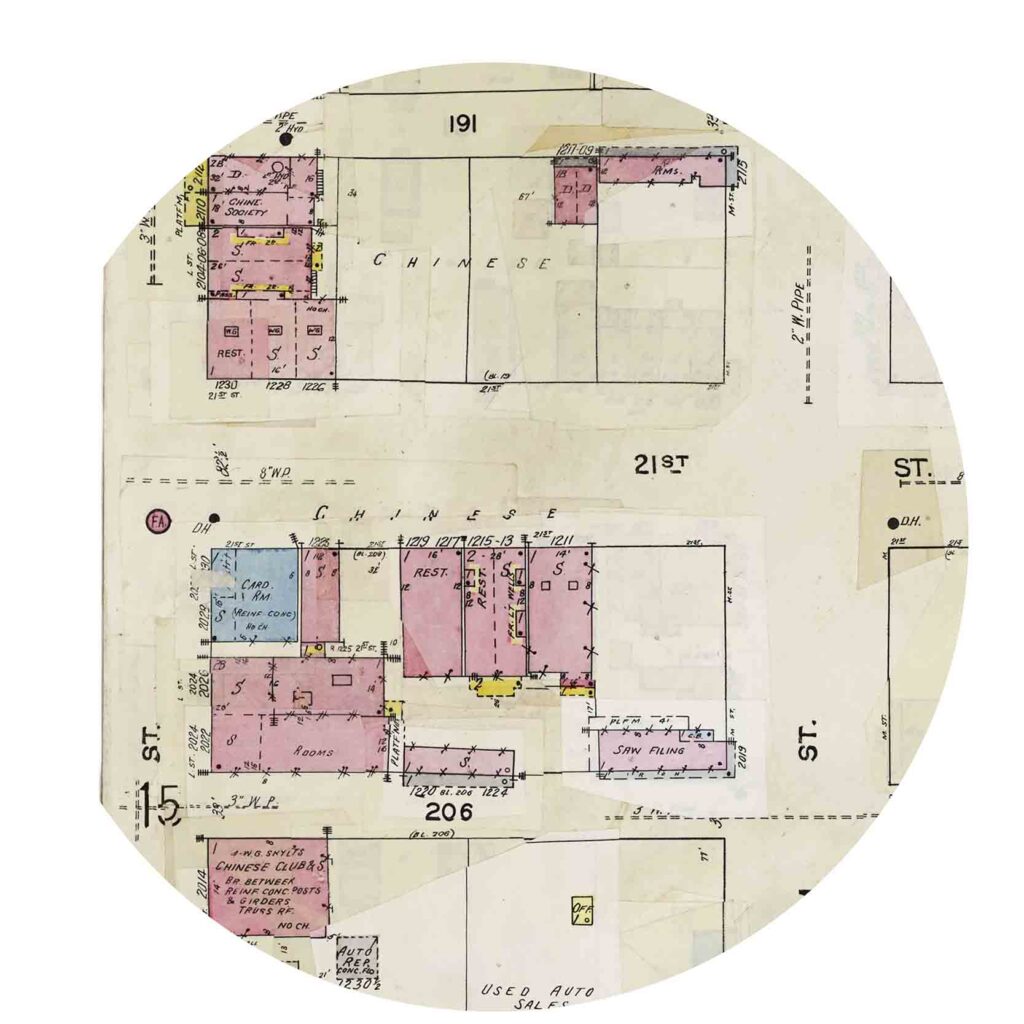

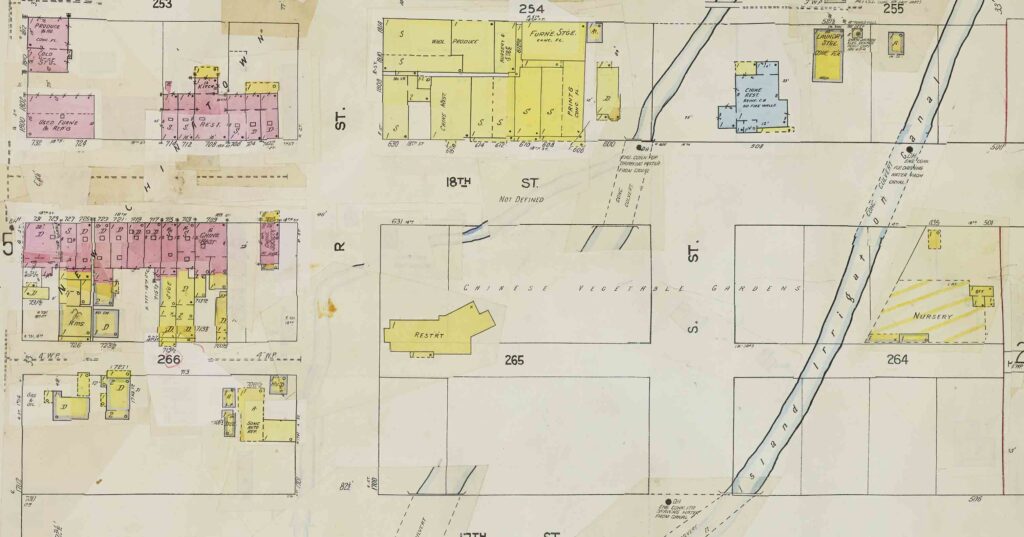

Local historian Diane Ogden notes how the current location of KGET was once the site of a religious temple and lodging house in the late 19th century, with a gambling hall located three blocks further south.1 This portion of downtown eventually became known as “Old Chinatown,” in contrast with the “New Chinatown” that was established several blocks further east. This Chinatown similarly had its own temple: originally a wooden building facing south along the river near 17th Street, it was replaced in the 1890s by “a new red brick building at the southwest corner of 18th and R Streets” – directly adjacent to the present-day downtown Antiques Mall and a block south of where the Bakersfield Museum of Art is now located.

The Chinese immigrants who settled in Bakersfield and other adjoining cities in Kern County in the mid-19th century arrived as part of a large workforce. While the first of these immigrants made their livings mining gold and quartz in the Kern River from 1859–1860, the next decade saw a further growth in the Chinese population due to laborers working on key infrastructure projects such as the Kern Island Canal in Bakersfield and the construction of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The railroad’s construction spanned all of Kern County from Delano to the Tehachapi Mountains, with this southern end proving the most dangerous as many immigrants lost their lives to explosives and cave-ins as they tunneled their way through.

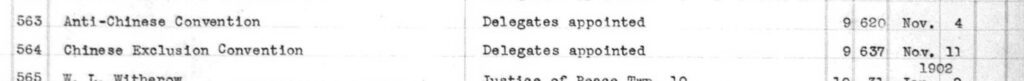

In the 1870s, the United States began passing laws regarding the exclusion of Chinese laborers, these laws were called the Chinese Exclusion Act; the basis for these Acts were the Naturalization laws. Beginning in 1875, the Chinese could only come here for work, and when they came to the ports the consul-general could decide whether or not to allow the worker(s) their permits. In 1882, the Chinese were seen as a danger to Americans and it was decided that the Chinese would be suspended from admittance into the US for a period of ten years. However, this law does not apply to the laborers who came to the US on November 17th, 1880 or laborers who come within ninety days of the passage of the law. Those Chinese laborers who stay in the US and decide to go out of the country for a bit must provide their name, occupation, last place of residency, as well as distinctive physical marks to a consul-general to be written down on a list. If a Chinese person was not a laborer and wanted to stay, the Chinese government would have to provide the correct paperwork to the US government, and any Chinese person found to be illegally in the country would be deported on order from the US president. On May 6th, 1882 No Chinese laborers, unskilled or skilled, would be allowed into the United States; this law also applied to Chinese miners. When the Exclusion Act expired in 1892, Congress extended it for 10 years in the form of the Geary Act. This extension, made permanent in 1902, added restrictions by requiring each Chinese resident to register and obtain a certificate of residence. Without a certificate, she or he faced deportation. The Geary Act regulated Chinese immigration until the 1920s.

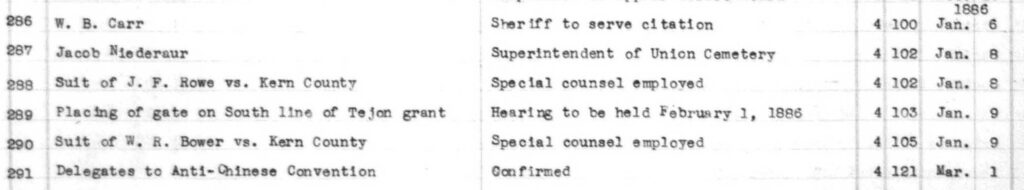

Unfortunately, Chinese immigrants’ willingness to work labor-intensive jobs such as these at low pay rates, paired with their growing population, led to tensions with Bakersfield’s white-majority community. An increased distaste was evident across class lines, as laborers feared that these immigrants would replace them and landowners feared that the same immigrants would lower property values. Growing discriminatory attitudes culminated in a town hall meeting on February 27, 1886, in which a resolution was signed by sixty-eight attendees, with another 200 names added within the following two weeks. This resolution reads in part: “Whereas, It is a fact that the Chinese are now and will forever remain a distinct and dangerous element, prohibiting forever the hope that the Americans can take them as neighbors or friends… Resolved, that it is the duty of all citizens having the general welfare of the Caucasian race at heart, and who, either from necessity or choice, are using Chinese labor, to replace it with Caucasian labor as soon as possible… The Undersigned hereby declare that we are in favor of the adoption of all lawful means for the exclusion of the Chinese from the Pacific Coast, and we hereby pledge that we will use every effort to secure white men to take the places now held by Chinamen, and that when they are thus secured we will not employ Chinamen, directly or indirectly, nor purchase the products of Chinese labor.”

As early as three years before this resolution, landowners such as the Carr and Haggin Land Company already began seeking ways to decrease their dependence on Chinese laborers, including the recruitment of African-American farmworkers from the South who were experienced in planting and picking cotton. By the time of the Dust Bowl, debates about the impacts of Chinese immigration had largely fallen by the wayside, as the Central Valley’s workforce instead became overwhelmed by an influx of migrants from the Midwest and Black migrants from the South. Despite these demographic changes, Bakersfield’s population of Chinese descent stayed resilient; having once been shunned and exploited, this population grew in social status in the following decades. By the time she wrote her essay in 1974, nearly ninety years past the discriminatory and highly racist city resolution, Ogden observed that many white residents in Bakersfield had shifted to a highly positive view of the Chinese-American community. Most notably, this opinion was shared by Bakersfield’s upper class, who were now “willing to live next door to them in some of the biggest houses and the most ‘elite’ section of town.”

With increased postwar immigration, Congress adopted new means for regulation: quotas and requirements pertaining to national origin. By this time, anti-Chinese agitation had quieted. In 1943 Congress repealed all the exclusion acts under the Mugnuson Act during World War II, leaving a yearly limit of 105 Chinese and giving foreign-born Chinese the right to seek naturalization. The United States intended to increase war moral, China was a wartime ally. The so-called national origin system, with various modifications, lasted until Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1965 after 80 years of exclusion.

How did the Chinese Exclusion Act affect Bakersfield’s Chinese residents?

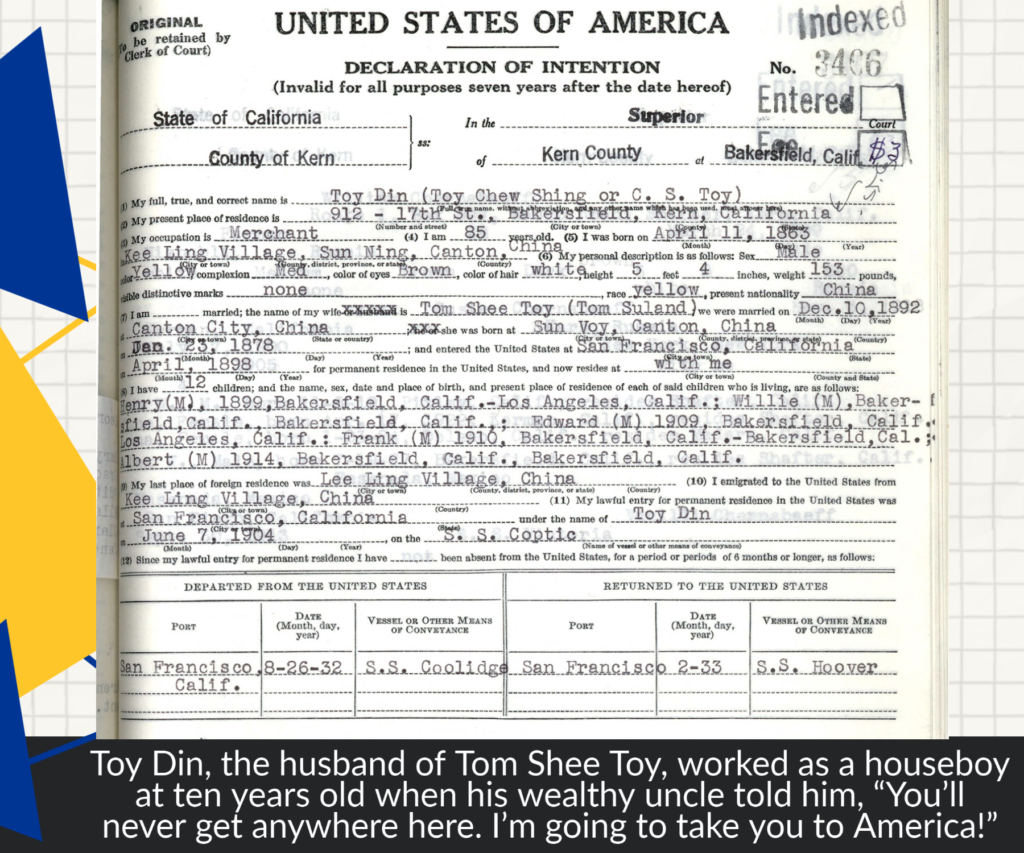

Toy Din, worked as a houseboy in Hong Kong at ten years old when his wealthy uncle told him, “You’ll never get anywhere here. I’m going to take you to America!” They immigrated through San Francisco in 1875. He worked at $50 per year for nine years before returning to China to marry Tom Shee Toy and returned to the U.S. in 1898 through San Francisco. The couple had twelve children, six sons, and six daughters. According to Tom Shee Toy‘s “Declaration of Intention,” she filed for citizenship, on January 15, 1948. In 1943, Congress repealed all the Chinese exclusion acts under the Mugnuson Act, leaving a yearly limit of 105 Chinese and giving foreign-born Chinese the right to seek naturalization. The United States intended to increase war morale because China was a wartime ally. The so-called national origin system, with various modifications, lasted until Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1965 after 80 years of exclusion. Din Toy operated the first store in “New Chinatown” which carried both Chinese and American groceries on the southeast corner of 18th and Q Street in Bakersfield. He later built the first large Chinese restaurant across the street, which was operated by their son George Toy. Din Toy (85) and Tom Shee Toy (69) naturalized in 1947. They naturalized 3 year after the repeal of the Chinese exclusion act.