Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – Covenant Database – East Bakersfield

Education – Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods

Public Housing – Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

Unequal Suburban Development

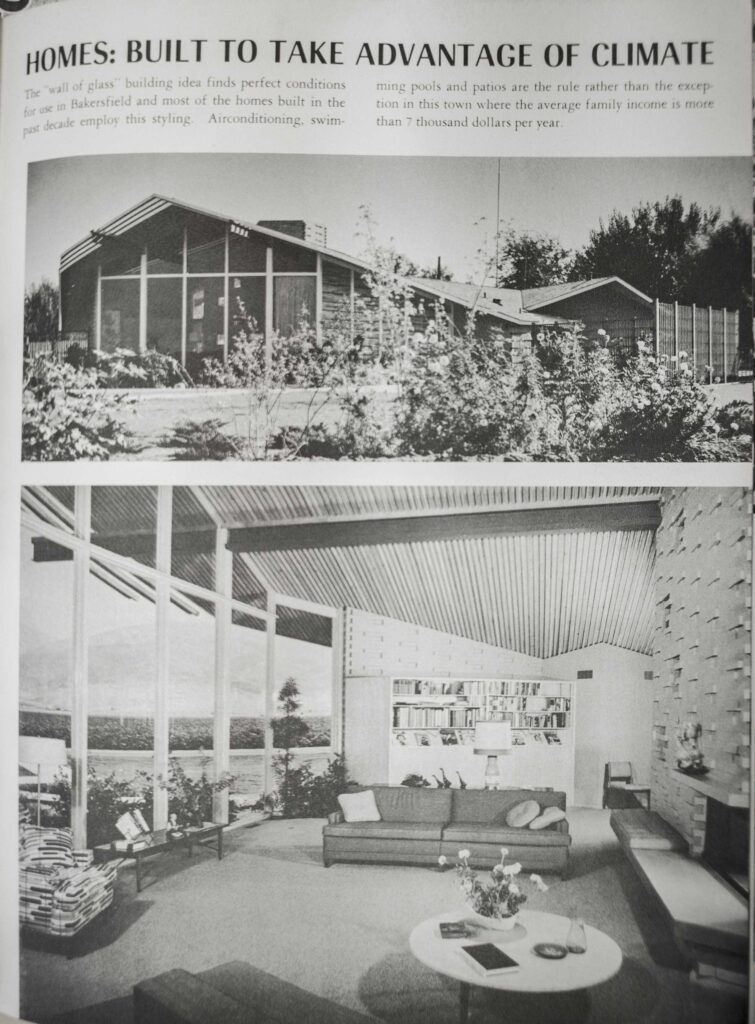

Starting in the 1940s, urban housing communities began construction in a new fashion, dubbed the modern urban and suburban model. The communities were farther away from downtowns, including older and centralized business districts. With time, these communities also created their districts to serve the needs of these auxiliary communities, resulting in new needs and investment in distant communities.

Bakersfield was a small but rapidly urbanizing city during this time. Between 1930s and 1950, Bakersfield had seen expansion to East Bakersfield, and expansion South-west Bakersfield (Ming and Stine). Bakersfield remains unique to western suburban history. While other older downtowns faced decline and lacked transformation, Bakersfield took the opportunity to rebuild and reimage it’s city scape after the 1952 earthquake. By the late 1950s, the city had a new court building, library, remodeled administrative buildings, an uplift to downtown, Bakersfield College was moved to its present day location (Panorama Drive), and all the elementary and intermediate schools were rebuilt. Click to view the E.E. Wonderly photographs of the damage cause to downtown Bakersfield.

Cruz, Donato. “‘America’s Newest City’: 1950s Bakersfield and the Making of the Modern Suburban Segregated Landscape.” ProQuest Thesis Publishing, 2020.

Federal Housing Administration, Principles of Planning Small Houses

1952 Earthquake: “Touring Downtown; pictures of Bakersfield immediately after earthquake”

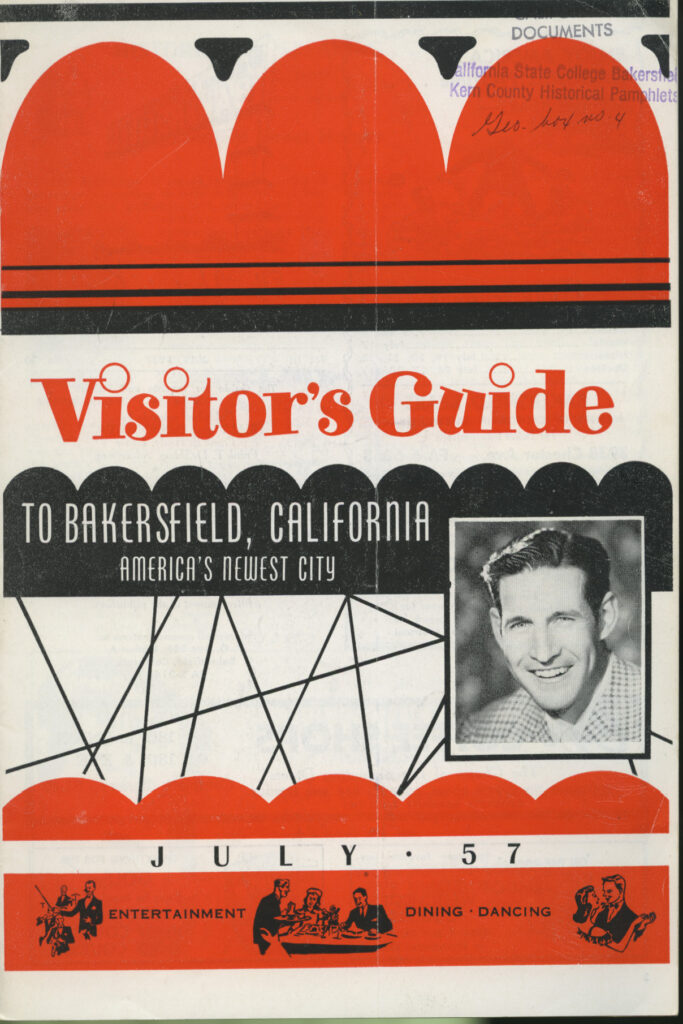

After the 1952 Earthquake, America’s Newest City Bakersfield

On August 22, 1952, an earthquake struck in proximity to the city of Bakersfield and by estimated accounts, generated about $10 million to $30 million in damage. There were reported fires, however, none further endangered the city and firefighters were called to dig out people who were trapped in collapsed buildings. As the days went on, engineers and contractors were hired by the City Inspector and instructed to survey and declare buildings unsafe. The city did not establish a policy on how homes should be repaired, only referring them to the City’s existing building code. The City of Bakersfield took no financial obligation to rebuild or renovate housing, nor was its intention recourse to help homeowners in the disaster. While no figures were reported for housing damage, official reports did mention housing. The “Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America: An Engineering Study of Southern Californian Earthquakes of July 21, 1952, and its Aftershocks,” reported on the types of damage homes sustained. The Engineering Study reported that wooden framed houses fell off their foundations if they lacked foundation bolts.

The city that rose after the earthquake became an invitation for a “white economy” and exclusively elite housing. Shortly before the “America’s Newest City” platform, welcome housing booklets were distributed to new homeowners. The welcome booklet included coupons, welcome messages from business owners, and a list of babysitters. This booklet also featured a personal and a very warm welcome from the Mayor, Manuel J. Carnakis. It read, “A hearty welcome to you from the City of Bakersfield. May your stay be long and happy… We hope you will join us with our civic affairs and social affairs. Get acquainted with our municipal problems. You are invited to attend meetings of the city council…” As the pamphlet welcomed the new homeowners, there was no mention of race relations, and yet, the map provided excluded the Mayflower and Sunset Tracts. The welcome seemingly was not intended for the minority residents who were segregated.

The city also had a Bakersfield Hostess, Dottie Hiatt. Her message read, “Yes it’s been a pleasure calling on you in your new home, and… if you ever need a friend, if we can ever help you, CALL ON US….” The newest homes were not in Mayflower or Sunset, but in the new East, South and West Bakersfield. By late 1952, Bakersfield College was already being redesigned and planned to be relocated to the new North-east Bakersfield. Campus plans were drafted in 1951, but the economic urban renewal investment of the post-earthquake accelerated its relocation. By 1954, most of the college’s buildings were approved for construction, and a 3.4-million-dollar contract was already awarded. New housing and higher education were being built for the elite communities. The college, while in the north-east, was not built to serve the minority and poor neighborhoods, a geographic feature that deterred public access to education and economic uplift. After the expansive urban renewal of the mid-1950s, Kern County advertised its public education as, “Good Schools, Good Citizens,” which included 133 elementary schools, 18 high schools, and two junior colleges.

On August 12, 1953, President Eisenhower addressed a message to the citizens of the City of Bakersfield, as the urban renewal was already visible. Then-President Eisenhower wrote, addressing the noticeable physical and financial changes,

“Senator Knowland has reminded me that approximately one year has passed since your community suffered the devastation of a major earthquake. He has reminded me also with understandable pride- of the speed and extraordinary community cooperation with which you have rebuilt your county. I gladly take this opportunity to salute the courage and resourcefulness shown by Bakersfield Citizens. I share Senator Knowland’s pride in these remarkable accomplishments of our fellow Americans. May Bakersfield continue to thrive through the years ahead. I am confident that it will.”

William Knowland had been a long associate of Bakersfield. As a visitor to the area, it was natural for Oakland’s Senator to speak of the condition of Bakersfield. From 1953 to 1955, Senator Knowland was also the Senate Majority Leader and the Minority leader from 1955 to 1959. He was well-known in California and national politics, and as we saw in the previous chapter, an opponent of public housing.

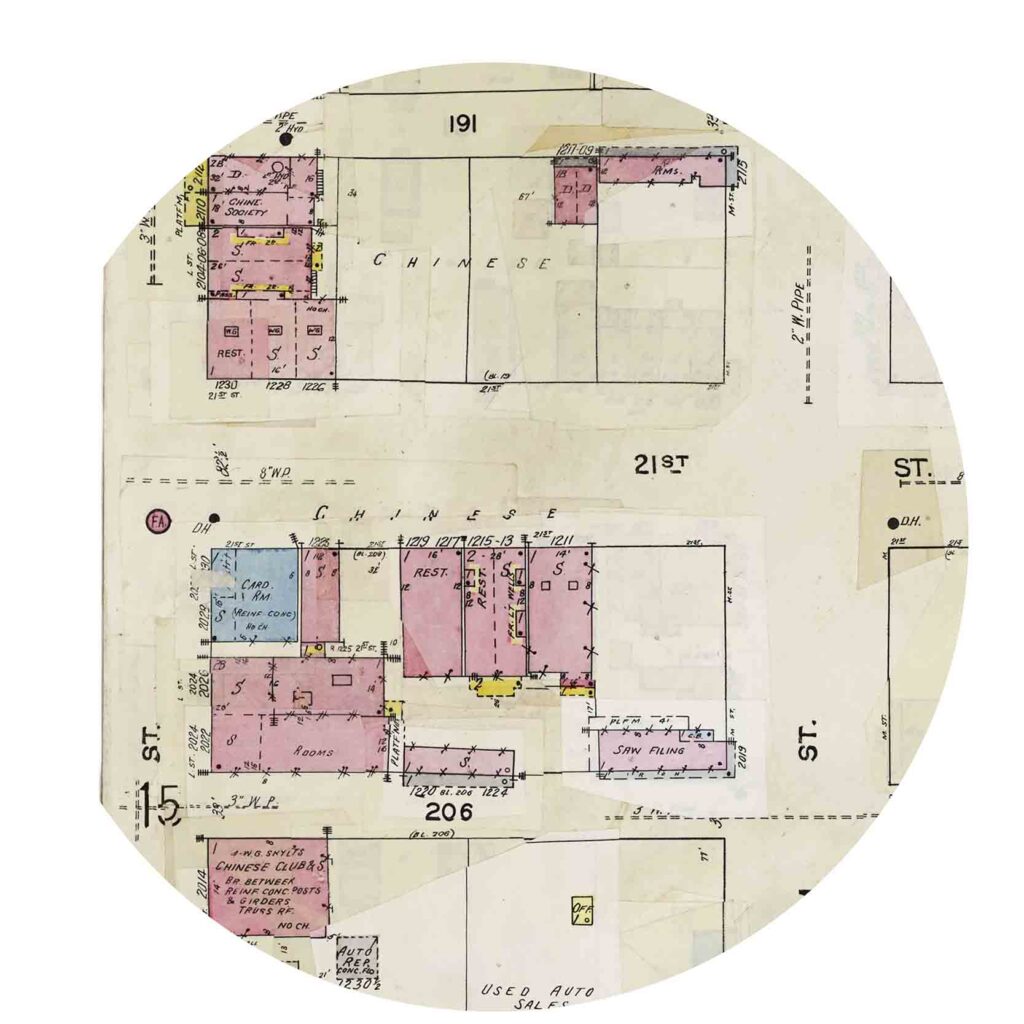

The City of Bakersfield was taking advantage of the earthquake in many ways. The Bakersfield Californian reported on August 23 1954 that a high percentage of “eyesore” buildings were gone. In the same light, the old downtown’s skid row was almost gone, following new construction. The city took full advantage of removing the sores they disapproved of and invested in removing buildings. The other history missing was how downtown redevelopment displaced people who were living nearby or in downtown. The impact proved to visitors that Bakersfield was a city that rebuilt in a “positive” direction and took an active responsibility in transforming. This is the only citation that suggests the removal of the Bakersfield Chinatowns, as city leaders remodeled downtown.

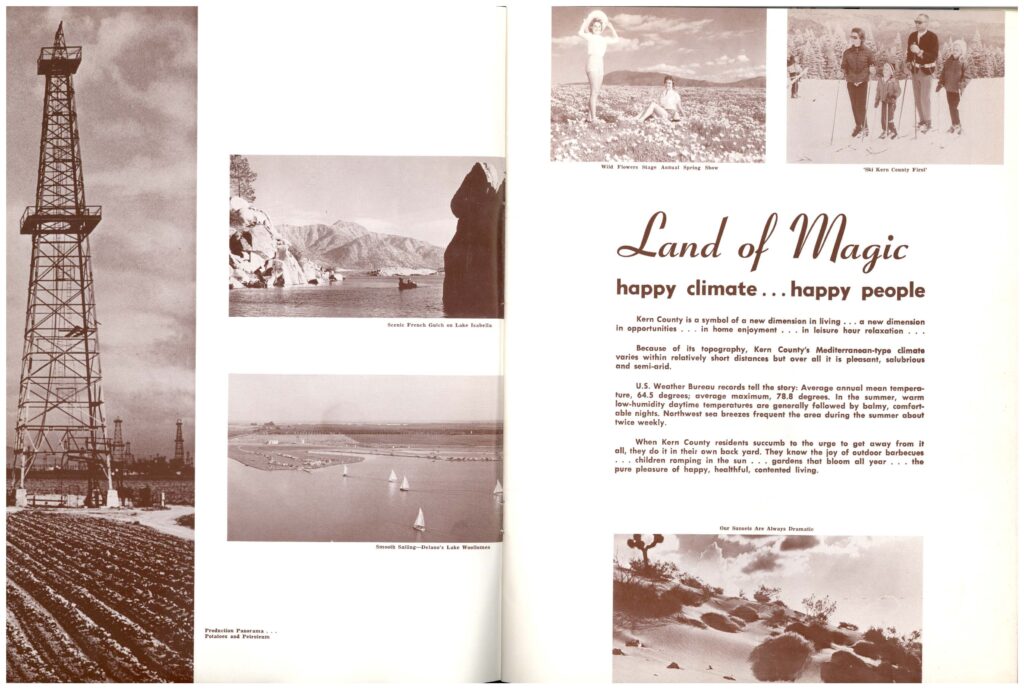

While the city of Bakersfield was rebranded as “America’s Newest City,” the County of Kern was marketed as the “Land of Magic.” These platforms of investments included new investments in tourism, business, education, and other economic transformations that did not include neighborhoods of color.

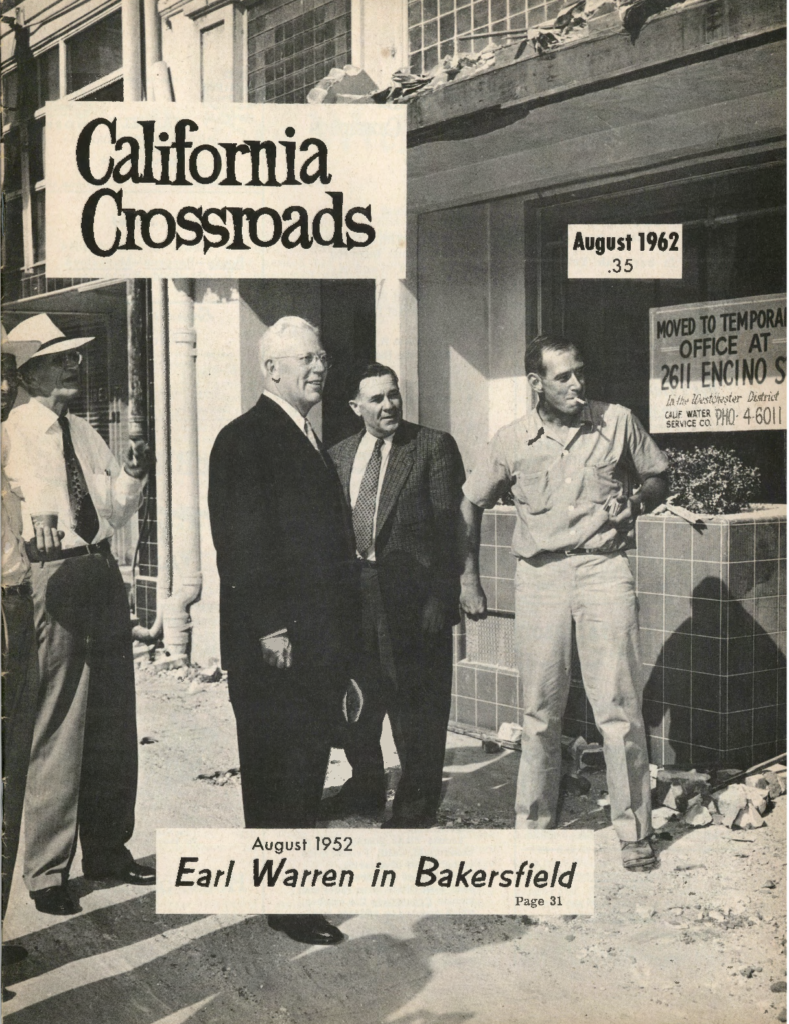

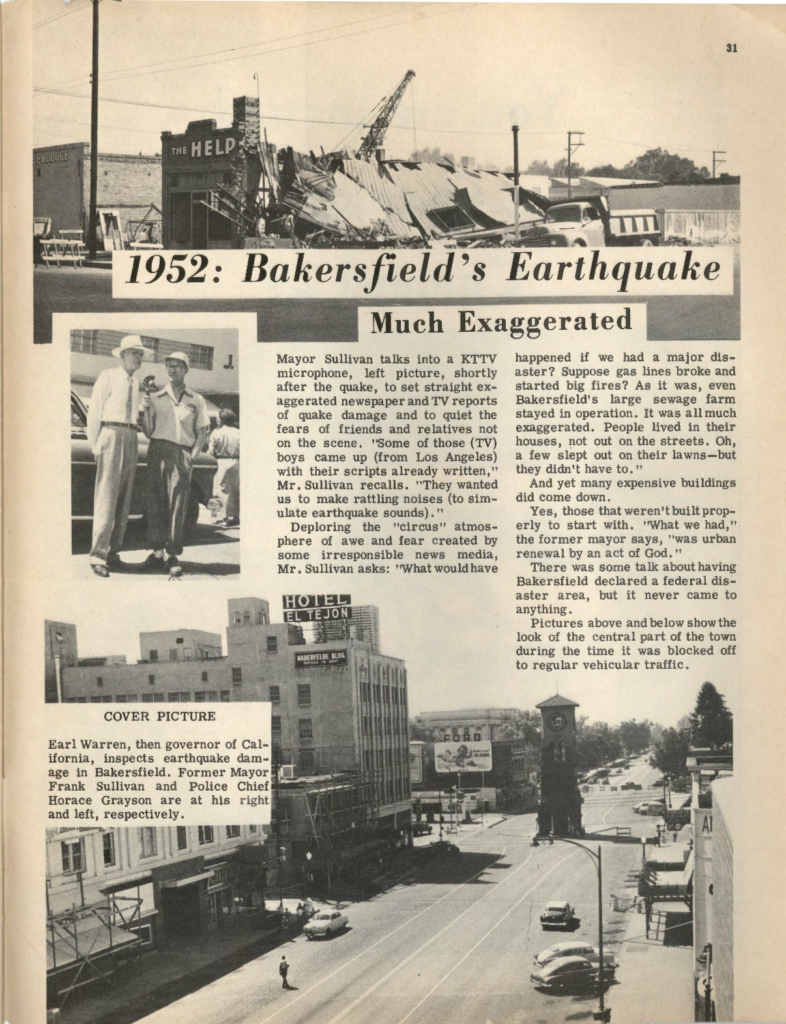

On the tenth anniversary of the 1952 earthquake, California Crossroads dedicated its cover feature and a full-page spread to the remembrance of the earthquake and rebirth of the City of Bakersfield. The photograph on the cover was of then-Governor of California, Earl Warren. He was photographed near a building with small amounts of rubble still on the ground. On his left was former Mayor Frank Sullivan, and on his right was Police Chief Horace Grayson. Frank Sullivan, who was mayor during the earthquake, gave some distinctive remarks on the anniversary of the transformation of the city. He recalled his interactions with out-of-town media and described the exchange as a circus, stating, “They wanted us to make rattling noises (to simulate earthquake sounds).” He seemed to be displeased in his reflection of the events that had “destroyed” the town. Sullivan asked, “‘What would have happened if we had a major disaster?’” Regardless of Sullivan’s calm demeanor, he was reflecting ten years after the initial rebuilding of Bakersfield, and as a previous mayor. During his reflection, he commented, “What we had was urban renewal by an act of God.” Those words resonated with the platform to rebuild Bakersfield, and launched the new marketing campaign of “Bakersfield, America’s Newest City.” The act of God was Sullivan’s opportunity to rebuild and reimagine the city since he was mayor in from 1950 to 1952 and again in 1957 to 1961. He took full advantage of it.

August Volume IV No.8, 1962. California Crossroads Magazine, 2019-005. California State University, Bakersfield, Walter W. Stiern Library-Historical Research Center. https://archives.csub.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/4799 Accessed February 09, 2024.