Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – Covenant Database – East Bakersfield

Education – Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods

Public Housing – Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

Public Housing

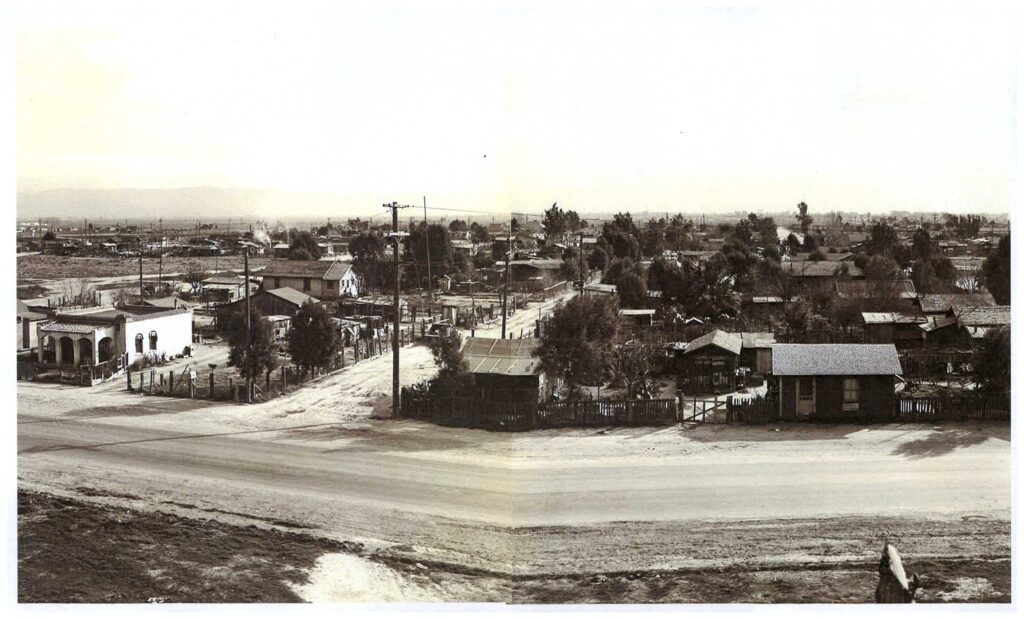

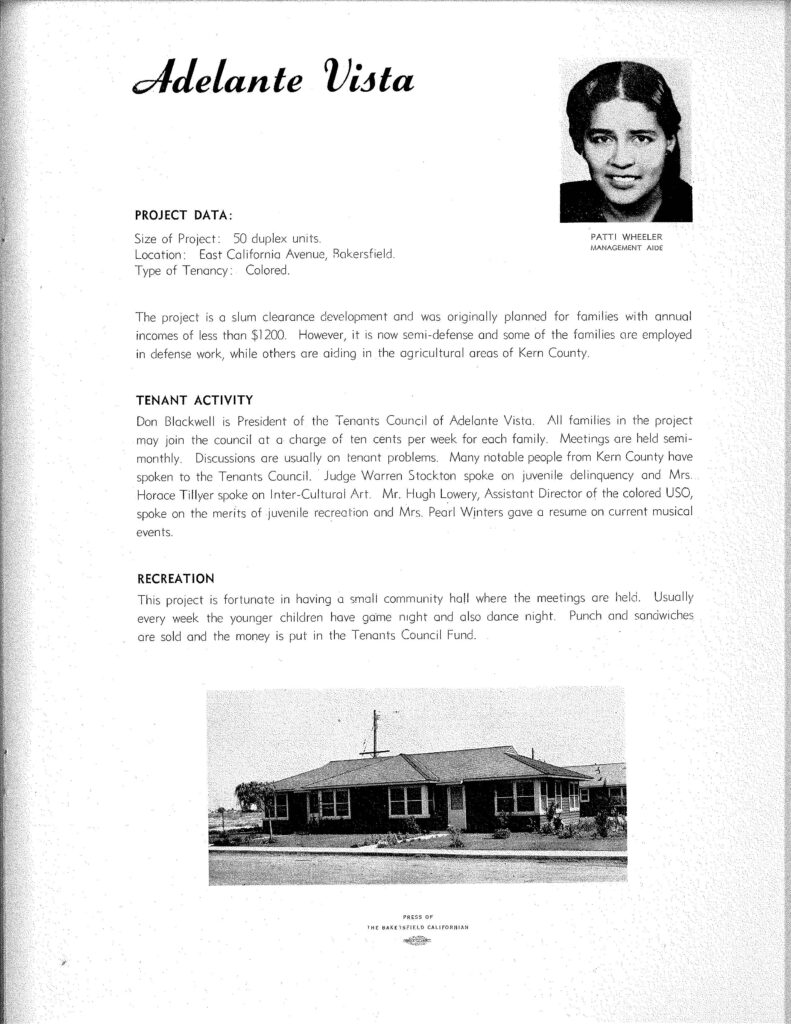

Public Housing in Bakersfield shares a similar fate to other California communities. Older minority neighborhoods often received less urban investment, of which destruction or purchasing under eminent domain was more likely. Adelante Vista, a public housing community in East Bakersfield, still stands and functions today as a public housing community. Adelante Vista was built over an older community and purchased through eminent domain.

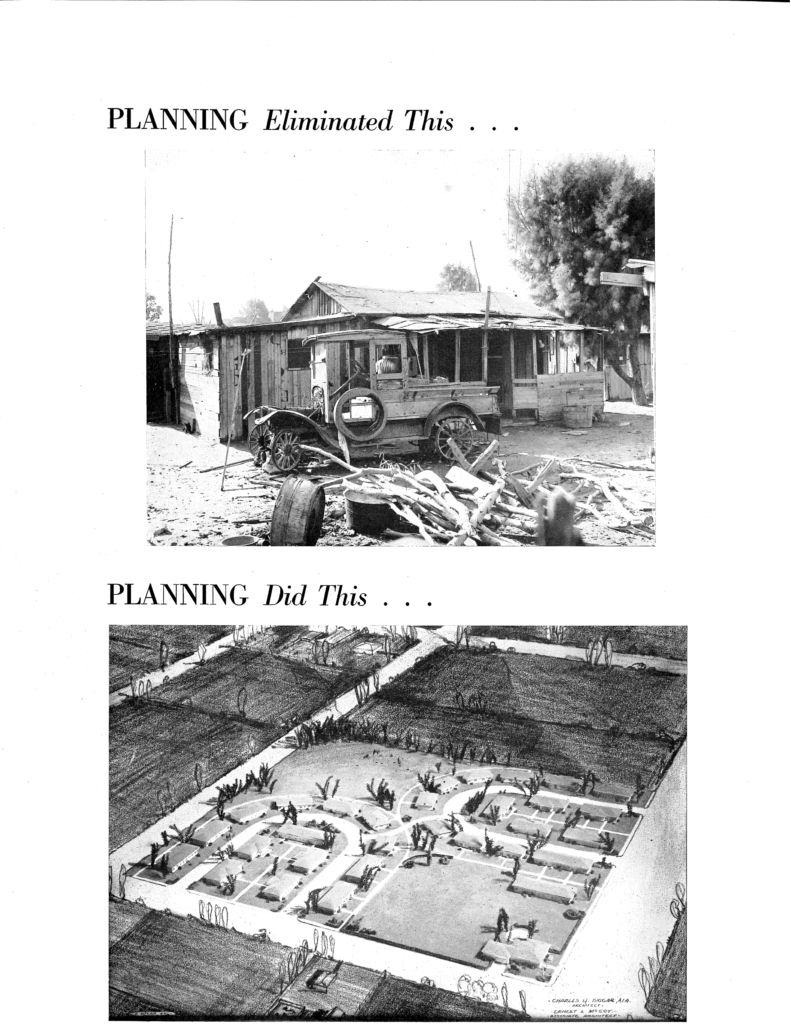

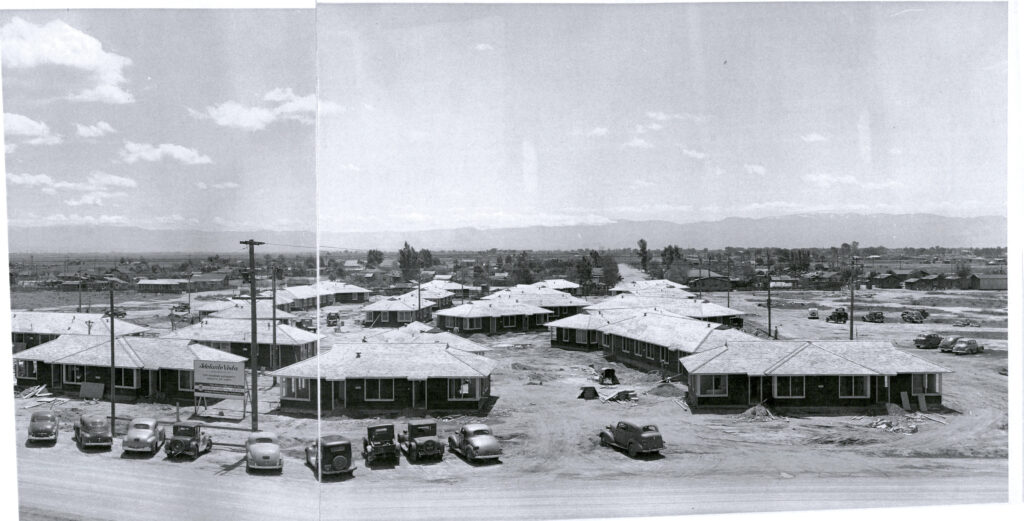

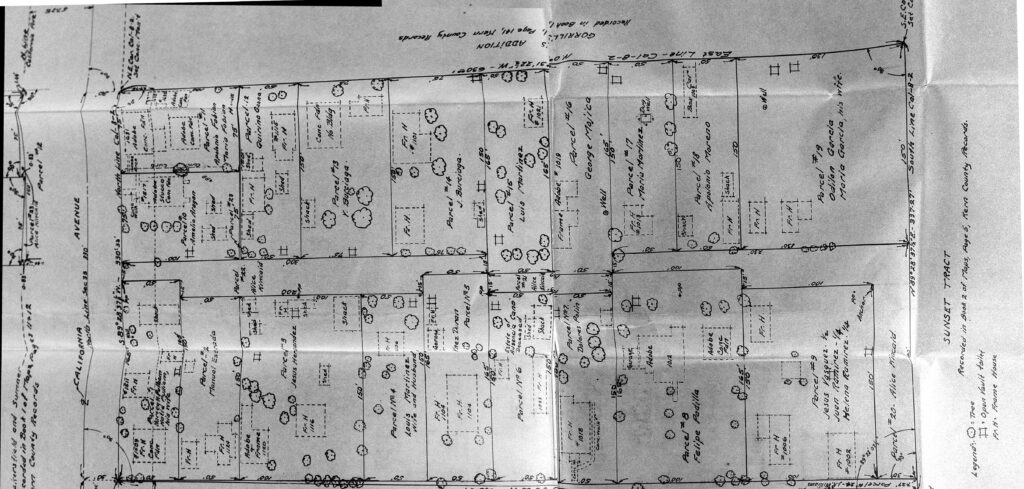

The first African American assisted housing was in the Sunset Tract, a low-density tract compared to Mayflower, which helped low-income families in defense-related industries. No public housing would ever be built in Mayflower, but instead in Sunset. Residents of Mayflower were housed in the public housing units built in the Sunset Tract. The first duplex unit was Adelante Vista in 1942. Families qualified if their yearly income was less than $1,200. Each year the Housing Authority produced reports on surveys conducted, money used, and new developments. By 1943, most families were in defense-related labor or aiding in agriculture. All the units and communities were built under the Housing Authority of Kern County’s vision of suburban modernity and desirability. Suburban renewal displaced many of those who lived and worked on farmland. Hispanics experience displacement at the Hick’s Camp in El Monte, Los Angeles County. Many workers were Latina/o/x renters who worked in the Hick farms. As they lacked real property ownership, even if the camps had little modern features, they were removed because they were substandard. Most minorities were victims of urbanization’s mission to eradicate substandard housing, which was simply called “urban renewal.” This effort took the positive characteristics of modernity and urban development since modern changes were not a universal experience; this came at the cost of minority renters and homeowners.

Affordability did not always translate into equal housing, sanitary, or modern amenities. Modern infrastructure came at the cost of many minority populations. This instance in El Monte was similar to what happened in Chavez Ravine. The neighborhood of Chavez Ravine had been acquired through eminent domain to build public housing. As Hispanic families were evicted, subsequently, the City of Los Angeles decided that the vacant properties would become the home of Dodger Stadium. The City used eminent domain to acquire properties, and as they became owners, they invested in urban development for tourism and industry. They had no real interest in building minority housing.

In 1942, Adelante Vista was the only African American public housing structure. In 1945, the Negro Handbook, a collective resource for African American housing and statistical figures, cited Adelante Vista as a permanent public housing facility for the Black community. Segregation of state and federally subsidized public housing was no secret. The 1940s projects were Cal 8-1 Rio Vista (Roberts Lane), Cal 8-2 Adelante Vista (Sunset Tract), Cal 8-3 Valle Vista (Delano), and Cal 8-4 Monte Vista (Arvin). In the 1943 Housing Authority report, all public housing other than Adelante Vista stated that their occupants were “mixed,” while Adelante Vista was labeled as “Colored.” The label “race occupancy” on formal reports said the clear difference between “mixed” and “colored” occupancy, which influenced race relations in public housing in the 1950s. Mixed most likely meant integrated, and colored, segregated. Oro Vista, the future public housing units built adjacent to Adelante Vista in 1954, remained African American. The sites had been selected by 1950 but were pending the Public Housing Administration’s approval of the proposed development programs in 1951. These projects for the 1950s followed Cal 8-5 Aero Vista (Oildale), Cal 8-6 Oro Vista (Sunset/Mayflower), and Cal 8-7 Terra Vista (Shafter). Oro Vista was the first large-scale public housing complex in the area and would house Mayflower and Sunset residents.

The public housing projects were given Spanish names, even when they were created to serve the African American community. The Sunset structures were named Oro Vista (Gold View) and Adelante Vista (Forward or Future View) to label these structures as a positive solution to the housing discrimination and shortage, but public housing was never meant to be permanent, nor had policies in place to protect equality. The Sunset-Mayflower public housing projects carried heavy negative connotations, especially in the fight that followed to stop the opening of Oro Vista from 1950-1954. “Public Housing” or “Projects” also carried a negative connotation in the national conversation. The Housing Authority built Oro Vista when reports told of the vast homes of Kern County in a dilapidated state, published in the 1950 Census of Housing report Special Tabulations for Local Housing Authorities. While these housing projects were built to alleviate the well-known housing situation, the orchestrated fight that followed in 1951 and 1952 did not help provide income or wealth access to residents of Mayflower.

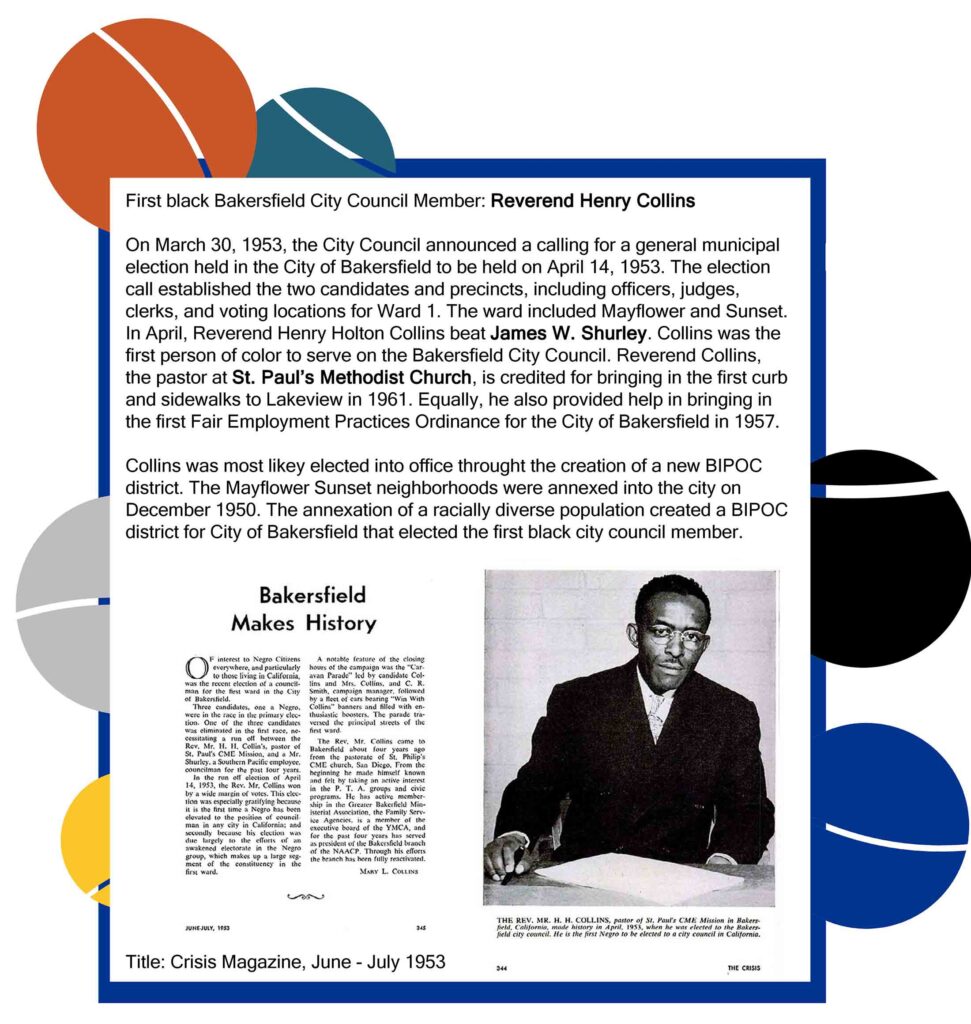

Councilman Henry Collins, the first African American to hold an elected position in the City Council (Crisis Magazine June 1953), had reported to the Bakersfield Californian that Oro Vista had come to be a disappointment to the residents. The homes were to house 184 families, and with an estimated 800 applications, only a small fraction had moved. The newspaper reported that by mid-February 1954, only 17 families had moved into Oro Vista. Collins complained that the application process was too rigid and strict, limiting opportunities and access; he stated that people of irregular and lower income could not receive help. The narrow application window provided minimal access. There were also many restrictions beyond income. The application required families to have specific types of furniture, good credit, steady employment, and that the woman be a good housekeeper. Single individuals were barred from the application; only families could apply. Collins stated the obvious, “How can a woman prove she is a good housekeeper when she has no house to keep?” Regardless of Collins’s reflections, he supported the county’s plan to introduce substandard homes in Mayflower and Sunset. He stated, “I don’t like the looks of the housing deal. The city seems to be getting the run-around, and in the end, the people of Sunset-Mayflower will be left out.” Collins understood the politics of the city and perhaps saw little alternatives. He was right about the rigidity of segregation; long-term change and fair housing was far away from becoming a reality. Shortly after, the City Council crafted two urban renewal ordinances. The City Council was getting ready to legalize selling substandard homes to Mayflower and Sunset.

By early June, the Bakersfield Californian reported that all the homes in Oro Vista were occupied, with occupants being 90 percent African American and 10 percent Mexican. The newspaper even reported that two white families applied but never returned to claim consideration. This perhaps hinted at the segregated nature of the housing in Oro Vista. Ninety percent of all Oro Vista’s residents were from within the Mayflower and Sunset Tract in June 1954. The newspaper did not report the origin of the other 10 percent of residents. Oro Vista was segregated from the beginning, resembling the demographic of Adelante Vista, which was segregated and adjacent.

All the units and communities were built under the Housing Authority of Kern County’s vision of suburban modernity and desirability.