Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – East Bakersfield

Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods – Public Housing

Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

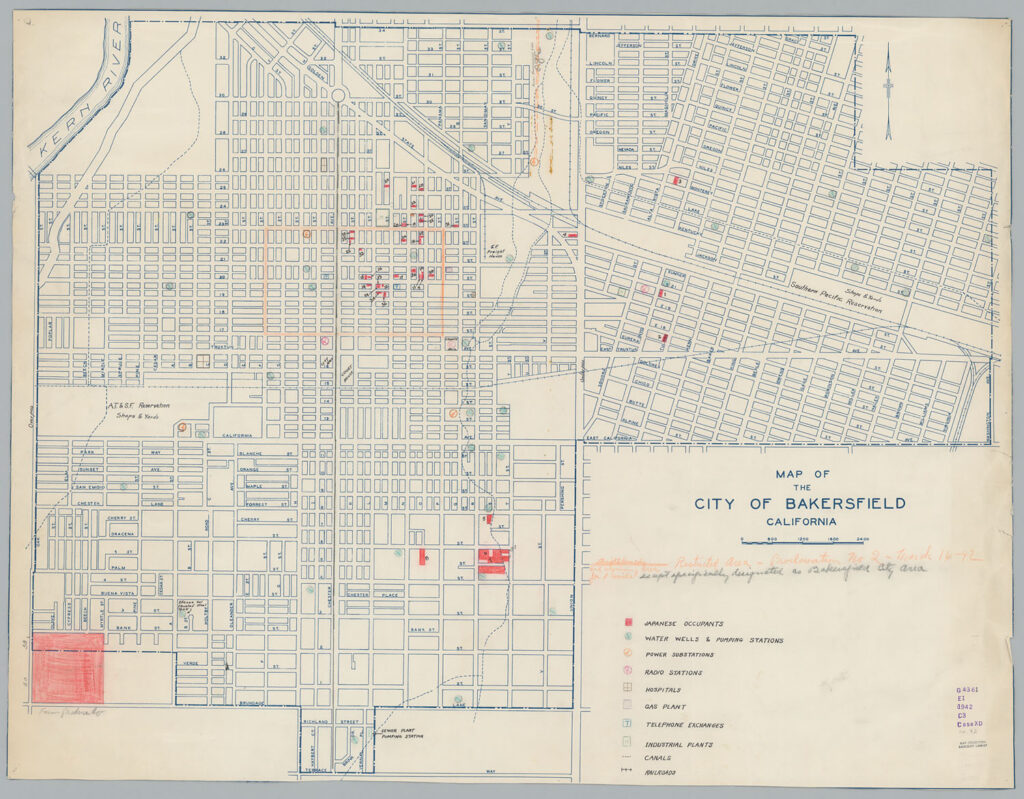

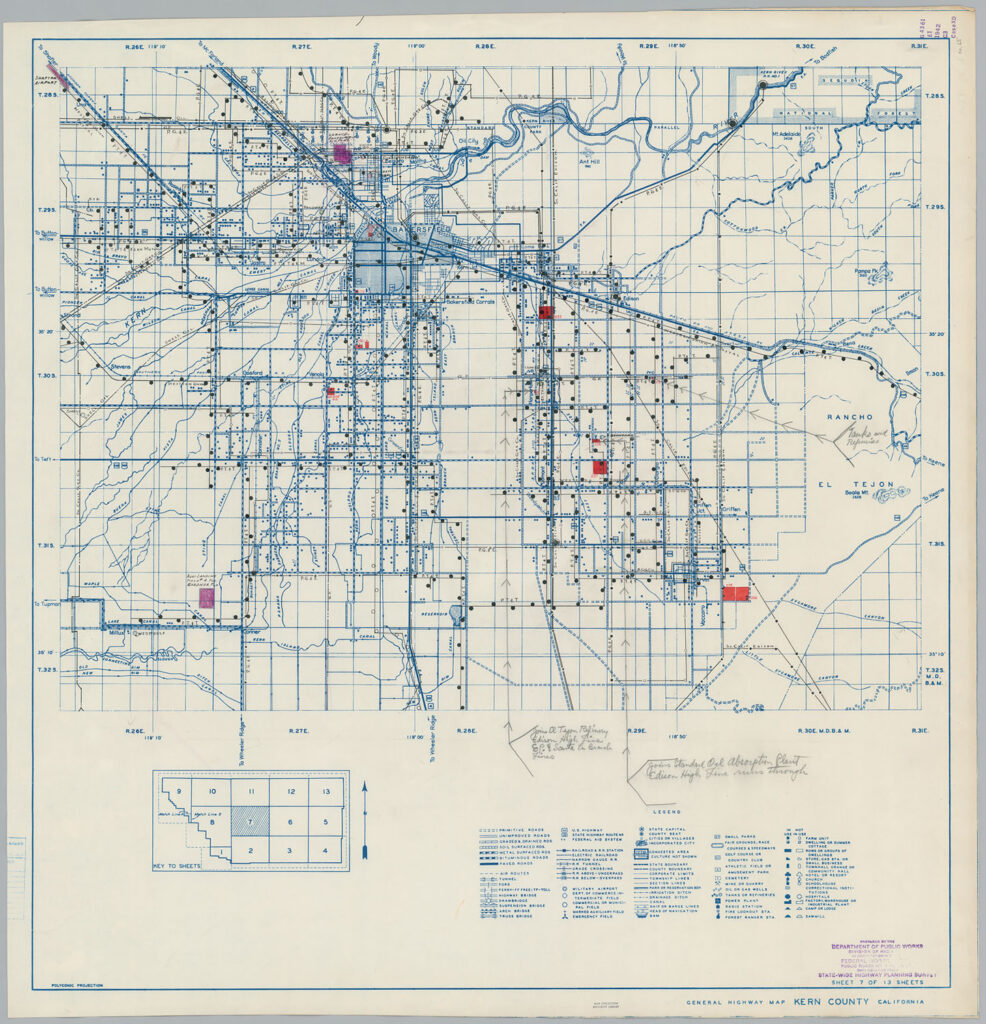

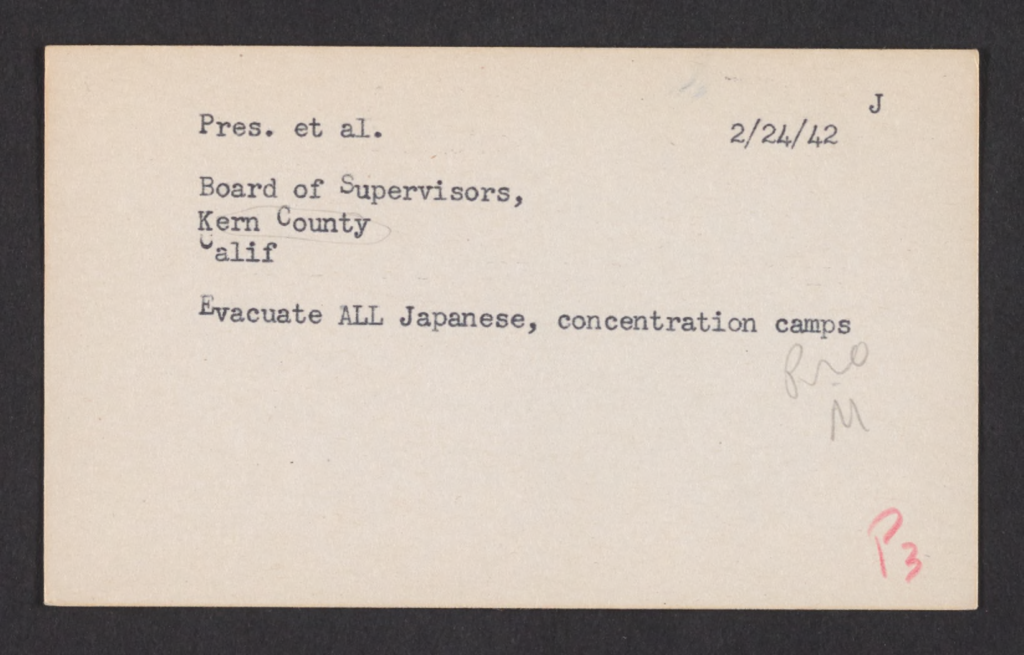

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor. The executive order authorized the War Department to designate military area. The order was neutral in language; however, it targeted more than 110,000 Japanese, relocating all persons of Japanese ancestry, both citizens and aliens, inland, outside of the Pacific military zone. Within weeks all persons of Japanese ancestry, whether citizens or enemy aliens, young or old, rich or poor, were ordered to assembly centers near their homes. Soon they were sent to permanent relocation centers outside the restricted military zones. Japanese were subjected to white hostility and laws were enacted to pull them from full participation in economic and civic life. Japanese immigrants, known as Issei, could not own land, eat in white restaurants, or become naturalized citizens. But the American-born descendants of Japanese immigrants, called Nisei, were citizens by birthright, and many had become successful in business and farming. Pearl Harbor gave whites a chance to renew their hostility toward their Japanese neighbors. The attack on Pearl Harbor also launched a rash of fear about national security, especially on the West Coast Civil liberties advocates brought lawsuits to try to challenge the constitutionality of Japanese relocation – but a timid Supreme Court refused to overturn the internment orders. By mid-1944, the government began to release some internees that they certified to be loyal Americans, but the majority remained locked up. The internees were ultimately released in January 1945, and many returned to their homes and tried to rebuild their lives. Some found that their homes had become occupied by strangers and needed to evict them in order to move back in. For many others, the years behind barbed wire had resulted in financial calamity, and they faced the daunting task of starting over with nothing. In 1948, the Federal government distributed a mere $37 million in reparations. During the Reagan-Bush years Congress moved toward the passage of Public Law 100-383 in 1988 which acknowledged the injustice of the internment. This was after 40 years of political agitation, Japanese Americans persuaded Congress to approve legislation providing an official apology and a payment of 20,000 to each surviving internee.

In April 1942, Frank Kawasaki, the president of the Kern County Japanese Association, was arrested by the FBI. Kawasaki was in charge of 150 Japanese workers on the DiGorgio Farms in Arvin. He was accused of sending money to Japan. Other legal cases included a California lawsuit to take land rights away from Japanese citizens. The case sought to take shares and financial interest from a Kern County farm and produce company that had Japanese American stockholders. 25% belonged to Tsunezo Kinoshita, J. Kubotsu Tanigaki, K. Tanaka, Irene Tanigaki, K. Kubostu, and Reymond Tatsuno.

Interment detainees formed sports teams organized by their former city residences. Bakersfield Oilers, Bakersfield AA Indians, Delano, was a sports team in Poston Internment camp. Many were also drafted and served in the US Army. Records from those relocated from Bakersfield stated they had some property and books in the Bakersfield Buddhist Church. 1943 reports state that personal belongings left behind were stored in schools and churches in Bakersfield and Delano, and they agreed to move all property to the camps, this included the Delano Japanese Language School. Others like Henry Hideo Miwa state that he had personal property left behind while living in caboose on the ranch of Frank Alexis, Bakersfield. Some died at the internment camps, and others went to school in internment camps.

Poston reports state that there were 134 individuals from Bakersfield in October of 1942. Daily activities were logged with extreme detail, only described as under constant surveillance. Two internees were watched under specific order, just for expressing leadership in their camps.

A local resident stated, “Then there will be bloodshed. Call it racial prejudice if you wish, but there is a growing sentiment against ever letting them return.” (1944)

In 1945, a Bakersfield biography was created describing the Japanese community. They took immense pride coming from Bakersfield; most had resided in the city for over 30 years, and the oldest being in the city for 45 years. They worked hard and were able to move up from laborers to owning businesses and owning farms. There were about 40 families before the internment. They had hotels, home laundries, and stores. Sixty percent found employment at the Santa Fe shops as machinists and mechanics. Forty percent found work as truckers for farming and found little competition. Most of the farm workers became owners and were well respected. They sold most of their merchandise locally and sold surplus vegetables in Los Angeles. They hired migrant Mexican labor.

They were sixty-five percent Buddhist, Shin sect. They held festivals celebrating special services and programs, and large participation created festival-size affairs. Thirty-five percent were Christians and was more popular amongst Americanized individuals. Friction existed due to recruiting.

Education was scattered through 16 schools in the city. Most students attended Kern Union High School, even after the construction of East High. They held high scholastic standings and were in 4-H farming programs. Most attended Bakersfield College. There were two Japanese Language schools. The Christian School taught one day, and the Buddhist school taught all weekdays.

The community had a mutual aid society, which contributed up to $100 dollars per contribution. They helped welfare for the Japanese, but also other minority groups. They also had a women’s group. They had recreation groups for Judo and Kendo (fencing). The community had different relationships with white friends, ranging from business school sports, but did feel excluded from integration. Bakersfield residents continued to voice against the returning of residents, but some had changed their minds due to Japanese American heroism in the war.

The impact of relocation:

Many farmers stored their equipment, some leased theirs with their farms, and many of them sold theirs at great loss due to the conflicting news distributed by different government agencies. The new volunteers were settled in blocks 6 and 11 at Poston [Arizona], but later arrivals were assigned to Blocks 14 and 19. Later, however, when the people became settled, some moved into other blocks. At present, they were scattered through Camp 1 Blocks 6, 11, 13, 14, 15, 19, 26, 30, 30, and 31. Correspondence with Caucasian friends is carried on to a certain extent, but the majority of the news about Bakersfield reaches Poston Through the Newspaper. Paul Higashi, Assistant Community Analyst

Reports, Nos. 23-28, 30-56 [Community Analysis Section], Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement records, BANC MSS 67/14 c, folder J3.21:2, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/k6571k17/?brand=oac4