Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – Covenant Database

East Bakersfield – Education – Eminent Domain

Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods – Public Housing

Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

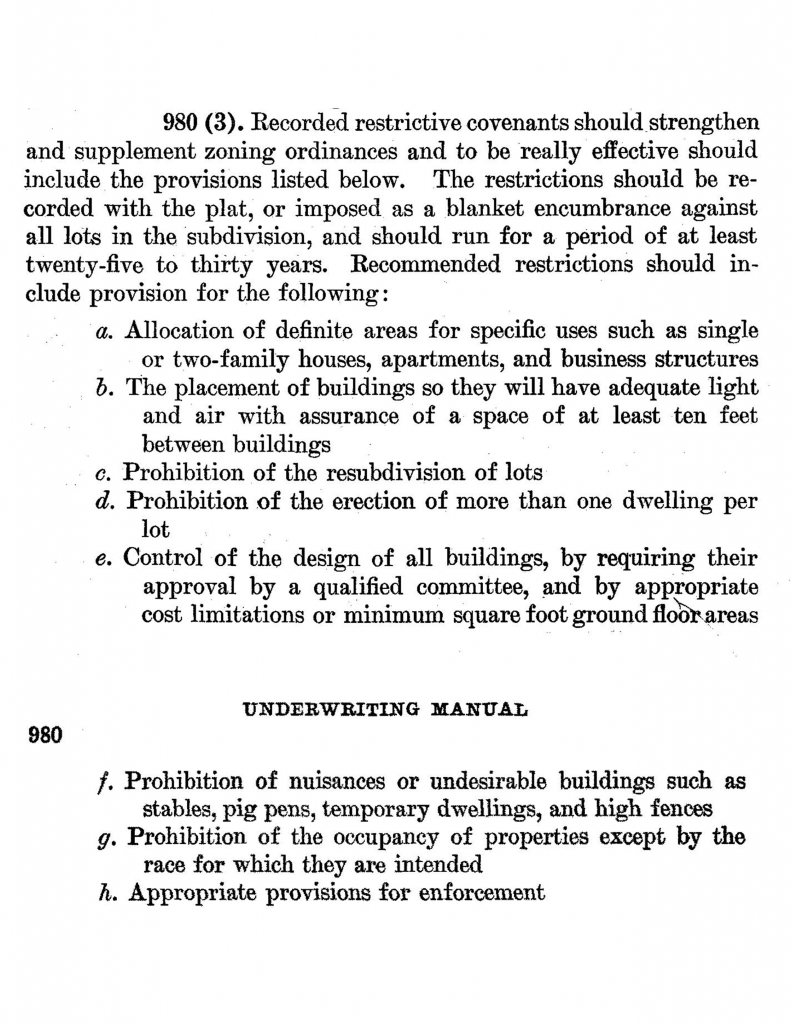

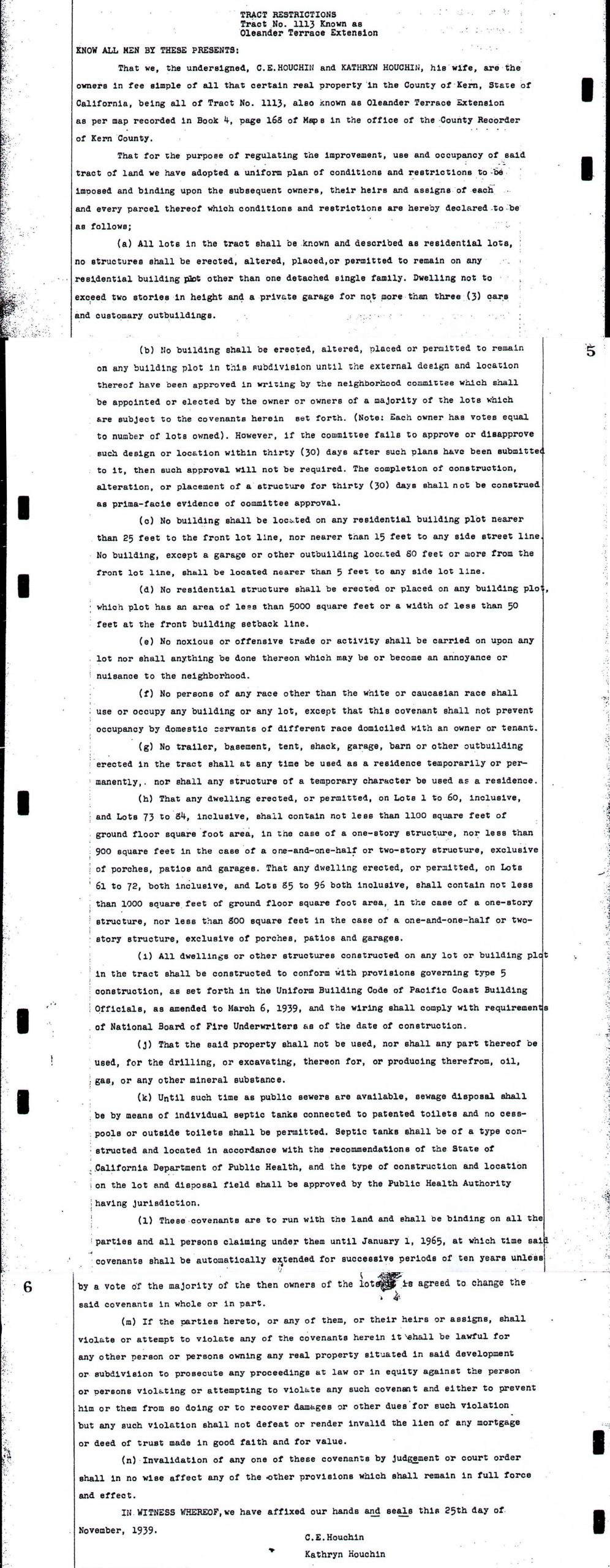

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) was established in 1934 as a New Deal Program. By 1938, the FHA Underwriting Manual recommended the use of racially restrictive covenants to developers and real estate agents to protect racial homogeneity within the realm of financial investment. To the left is a page from the Underwriting Manual, published in 1938. All covenants or legal agreements on the conditions of buying, owning, building, or selling homes were racially exclusive. These “agreements” were conditions of collective owning in neighborhoods. This style of contract was used all over the United States; examples are not limited to the American South and the Midwestern States and include the Urban North and the Western United States. There have been many historical analyses in states like Illinois and California. These case studies are used to show the type of racial segregation used in suburban and rapidly urbanizing rural communities outside of the “Jim Crow” American South. These restrictive covenants are sometimes classified under Agreement, Covenant, Covenant Agreement, Covenant Restrictions, Restrictions, Restrictions Amendments, Restrictions Declarations, and Restrictions Covenant Modifications.

Explore Racially Restrictive Covenant Database

The conditions and restrictions created limited geographic access to renters and homebuyers. The limitations created uniform behaviors, which were made to encourage racial and economic homogeneity by having visual similarities, usage, square footage, yard setback, and financial value. Modern homes can also have these constraints, but in the past, covenants banned certain races. Covenants also had additional limitations, as the tract’s restrictive agreements had multiple sections and specific bans contained within them. Ideas of desirability influenced the first nine sections of the legal agreement. Besides race, the rest were all economic limitations. For example, restrictions included limits on home use, where no trade work or noxious buildings were allowed on the property lot. Additionally, only single-family homes were allowed with neighborhood committee approval and minimum property value and square foot size. The categories allowed future owners and sellers to sell to the race and the socioeconomic class they approved. These restrictions had a profound impact on neighborhood demographics by limiting purchases to white middle-class families.

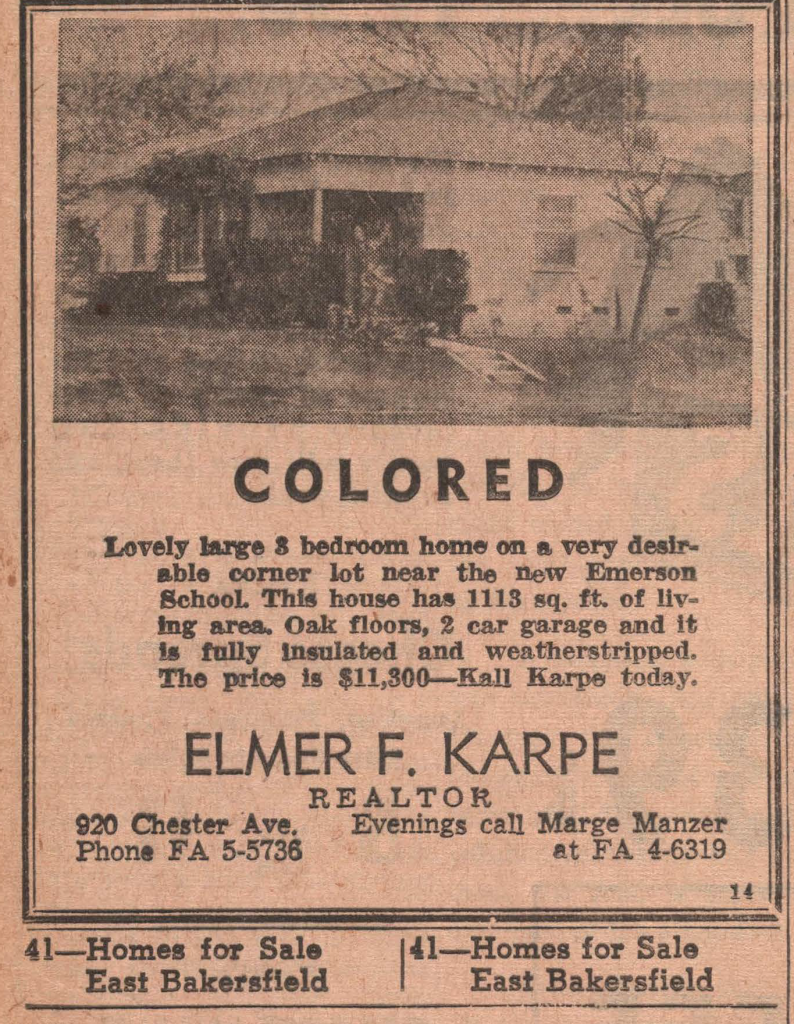

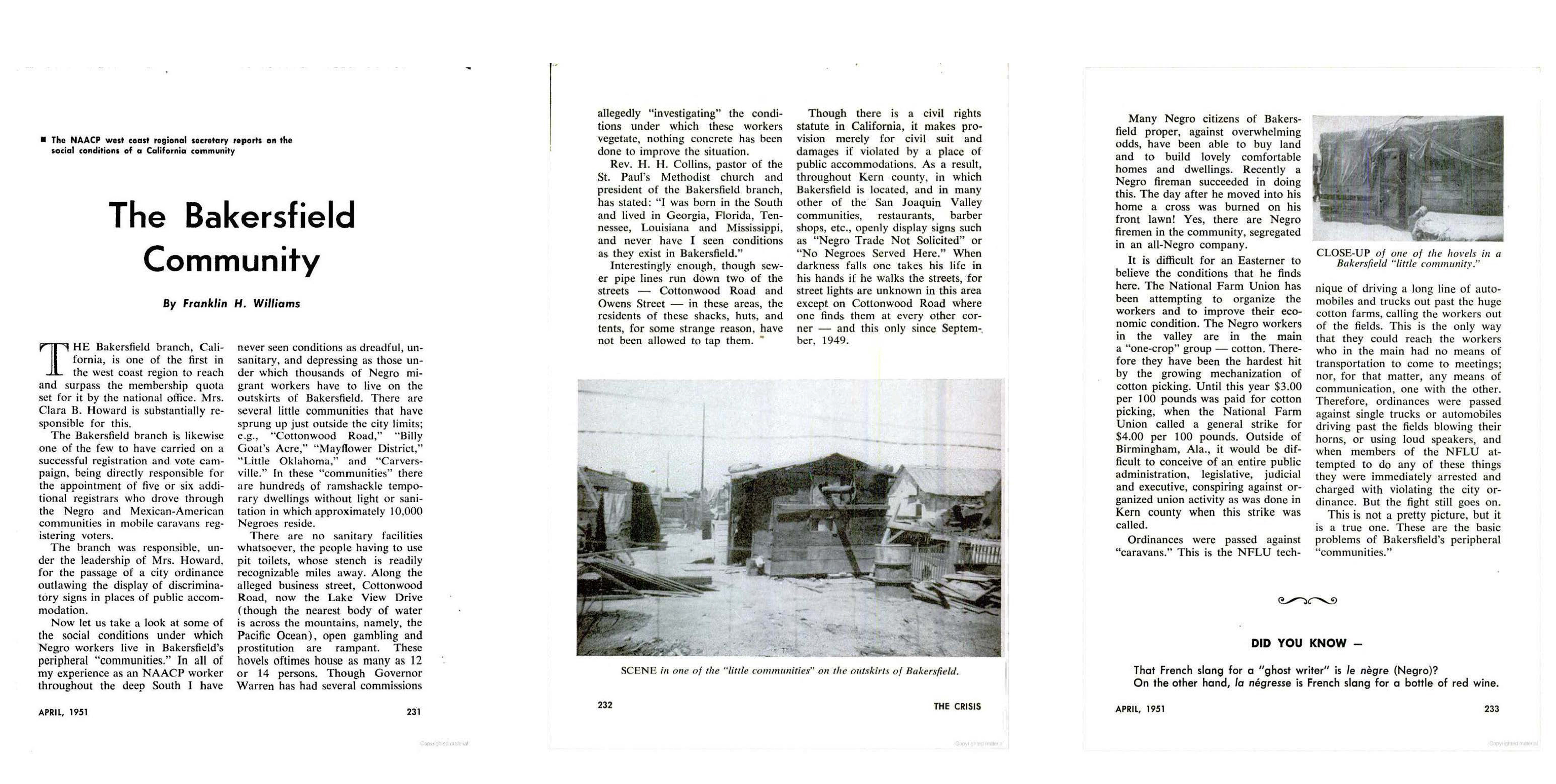

White only neighborhood communities proliferated because new homes were legally segregated. Racially restrictive covenants, legal agreements between sellers and buyers, forbade the selling of new homes to minorities. Legal race controls, in part, helped create minority-dense neighborhoods. These legal agreements limited opportunities for minority residents to leave older neighborhoods and limited the geographic availability of older and dilapidated homes. The opening of older neighborhoods resulted in more racially homogeneous tracts in this geographic space. Minority residents were often only given the option to buy in already minority-populated neighborhoods, which for the most part, did not offer the same modern sanitary facilities or modern investments. “White Flight” created housing availability and opened homes for sale. These markets, however, allowed for predatory lending and selling of dilapidated homes. These conditions of segregation had similar outcomes to the segregation of Jim Crow.

The Federal Housing Administration was established in 1934 as a New Deal Program. By 1938, the FHA Underwriting Manual recommended the use of racially restrictive covenants to developers and real estate agents to protect racial homogeneity in the name of financial investment. Below is a page from the Underwriting Manual, published in 1938. Community members can now request to remove racially restrictive language from deeds under Assembly Bill 1466 for more information visit https://www.kerncounty.com/government/departments/assessor-recorder/records/restrictive-covenant-modification

This webpage and research are based on Cruz, Donato. “‘America’s Newest City’: 1950s Bakersfield and the Making of the Modern Suburban Segregated Landscape.” ProQuest Thesis Publishing, California State University, Bakersfield 2020.

In 1948, Shelley v. Kraemer, a U.S. Supreme Court case held that courts should no longer be enforce racially restrictive covenants in real property deeds, which prohibited the sale of property to non-Caucasians. Racially restrictive covenants violated the equal protection provision of the Fourteenth Amendment. While Shelley v. Kraemer overturned the “court enforcement” of racially restrictive covenants, contracts still included race restrictions until 1950 when the FHA announced that it would not finance homes that had racially exclusive agreements. The effect was minimal. This did not end housing segregation and it was not until 1968 when the Fair Housing Act was passed, the last Civil Rights Act of the 1960s. Housing inequalities continue to this day.

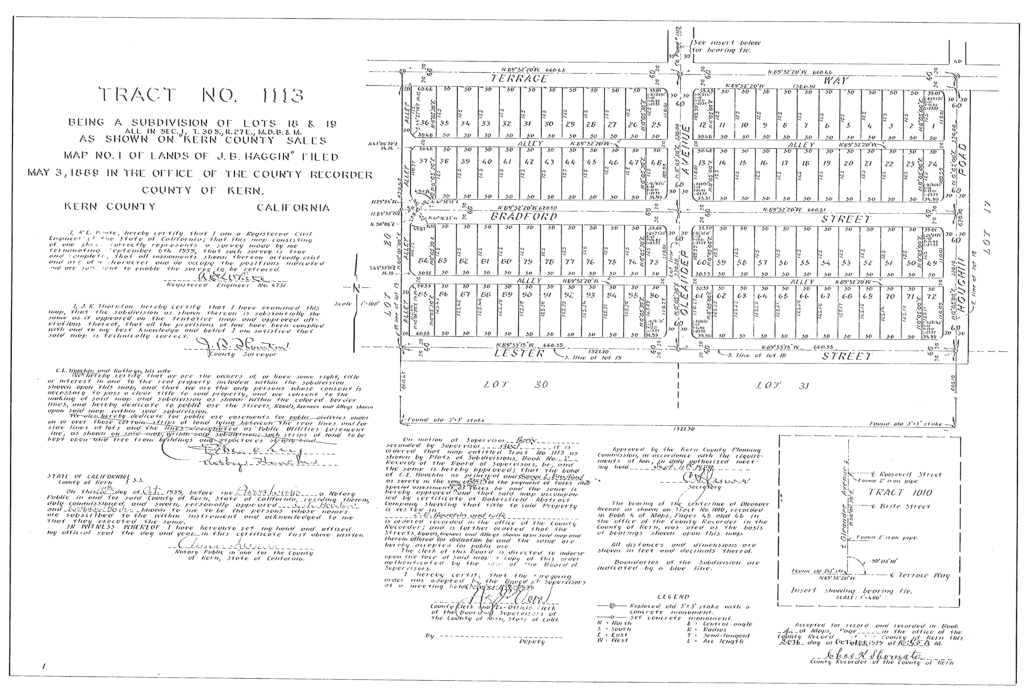

Between 1938 to 1950 there were an estimated 218 housing tracts built or had notarized racially restrictive covenants written in Bakersfield. While this research provides a glimpse to the vast racial segregation in Bakersfield, this research does not include individual housing racial restrictions that predate the FHA recommendation, nor does this research include other forms of racial segregation, or demographic research. The first racially restricted tract covenant was in 1938, Tract 1043, Rose Garden tract. Some tracts were older, but racially restricted covenants were not summited until after 1938, and some early tracts were re-subdivided during 1938-1950.

The Condition of Segregated Housing

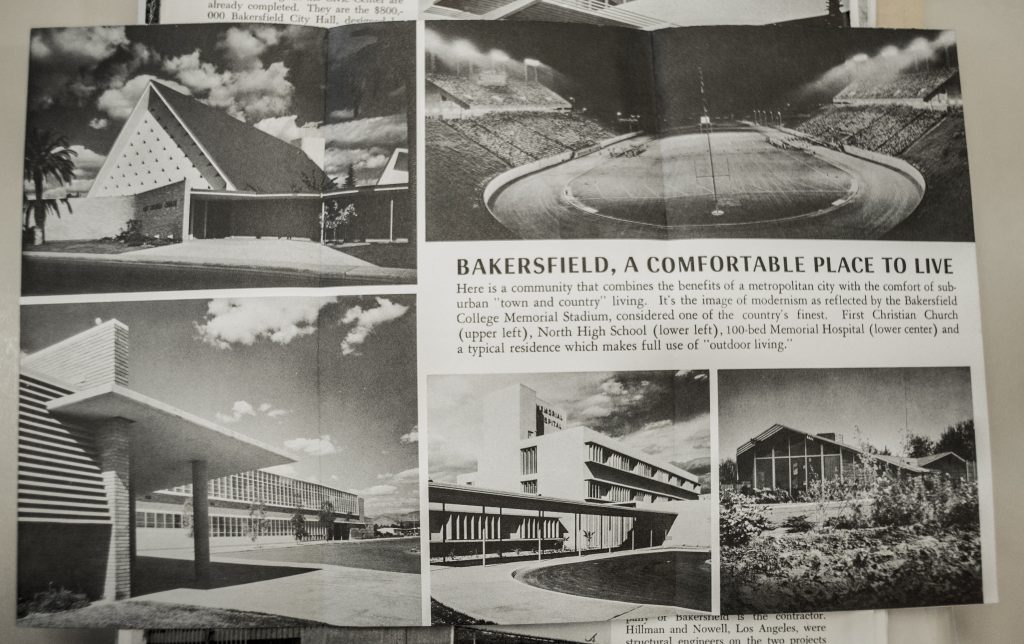

Unequal Suburban Development

List of all tracts organized by date of establishment, including developer names, covenant notarized date, and tract number or name. Explore the Interactive Map

Chris Livingston and Donato Cruz’s presentation, “Bakersfield Red Lining,” focuses on the HRC’s recent work documenting the history of racial segregation and housing policy in Bakersfield during the 1940s and 1950s. Based on the HRC’s current exhibit on the second floor of the Walter W. Stiern Library, this presentation will enlighten attendees regarding the history of segregation in Bakersfield, including innovative mapping being used to visualize race and space in Bakersfield. Includes the original song “Redlining Blues” by Gabriel Soria.

00:00:00 Introduction by Dr. Oliver A. Rosales 00:00:17 Introduction by Elizabeth Diaz, BC History Club President 00:03:34 Presentation by Chris Livingston, Historical Research Center 00:32:03 “Redlining Blues” by Gabriel Soria, a song about redlining in Kern County 00:35:37 Presentation by Donato Cruz, Redlining in Kern County 01:01:09 Questions and Answers

The story of Housing in California’s Central Valley has been one of exclusion, isolation, and destruction. This lecture will examine the history and development of “red-lining” and housing discrimination in Bakersfield and Kern County. It will also examine the primary sources that document this history and discuss the importance of critical examination of primary sources in historical research. Chris Livingston and Donato Cruz discuss redlining, research, and housing discrimination. Recorded October 11, 2023, Kern County Museum.

Kern County experts Donato Cruz, Jesus Garcia, Lori Pesante, Harveen Kaur, and Traco Matthews discuss the process and history of redistricting, their research and involvement in Kern County, as well as the effects redistricting, has had on BIPOC Communities. Panelists discussed the redistricting process and practice of redlining and how both affect BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities. Recorded October 20th, 2022, at the Kern County Library.

The Walter W. Stiern Library hosted an interdisciplinary panel discussion: “The Sound of Something Better,” A Legacy of Racial Injustice in Bakersfield. This panel addressed racial and religious inequalities in Bakersfield and surrounding communities. The presenters were Donato Cruz, Carolyn Lane, and Eileen Diaz. Topics included Bakersfield housing redlining. Recorded on October 26, 2022, at the Walter W. Stiern Library.