Education and Segregation

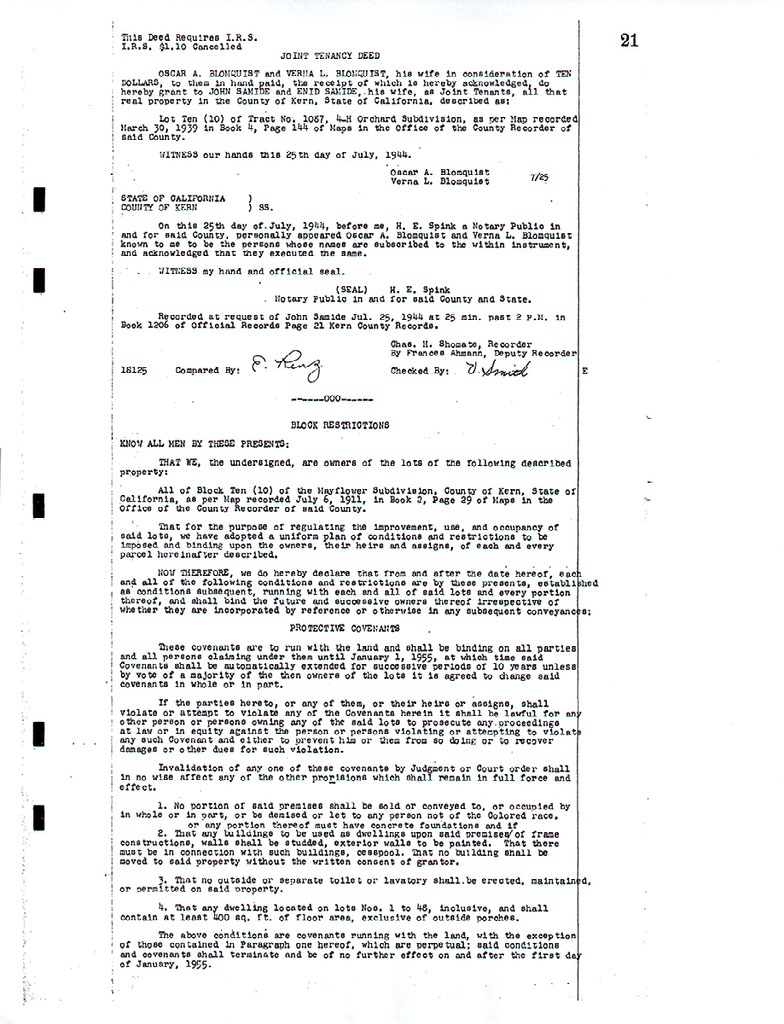

Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – Covenant Database – East Bakersfield

Education – Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods

Public Housing – Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

According to historian Colin Gordon, “Segregation reinforced inequalities in housing, education, government investment, trust, social capital, job opportunities, environmental hazards, crime, and job opportunities.” Housing Segregation had a deep impact on communities of color. The lack of resources and education quality ran parallel with housing discrimination. When real estate agents used the argument of “private rights” to deny citizens of color, their own rights, investments in the “redlined” neighborhoods often had unequal services and unequal demographics.

Gordon, Colin. Patchwork Apartheid: Private Restriction, Racial Segregation, and Urban Inequality. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2023. https://csu-bakersfield.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01CALS_UBA/1efqqi0/cdi_globaltitleindex_catalog_421066406

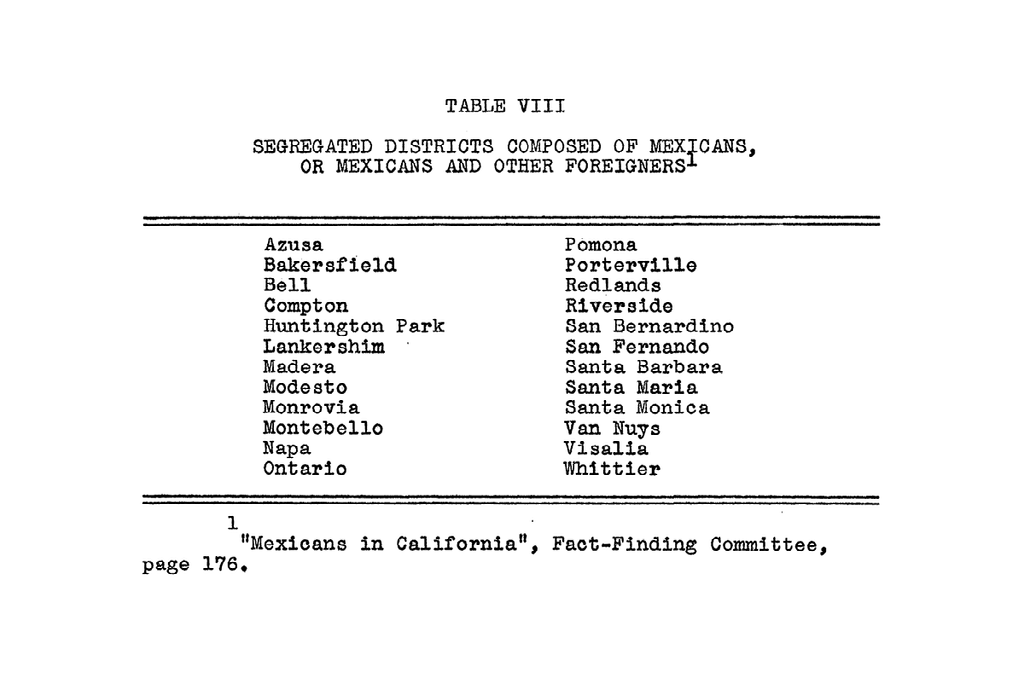

In a report conducted by the State of California in 1930 found that there were 24 out of 47 replies that cities had segregated Mexican Districts. The report states,

“In addition, other boards cited clauses inserted in deeds and sales contracts calculated to confine Orientals, Mexicans, and Negroes, to certain districts.” Bakersfield was already reported with housing segregation.

Mexicans in California; report of Governor C. C. Young’s Mexican Fact Finding Committee, 1930

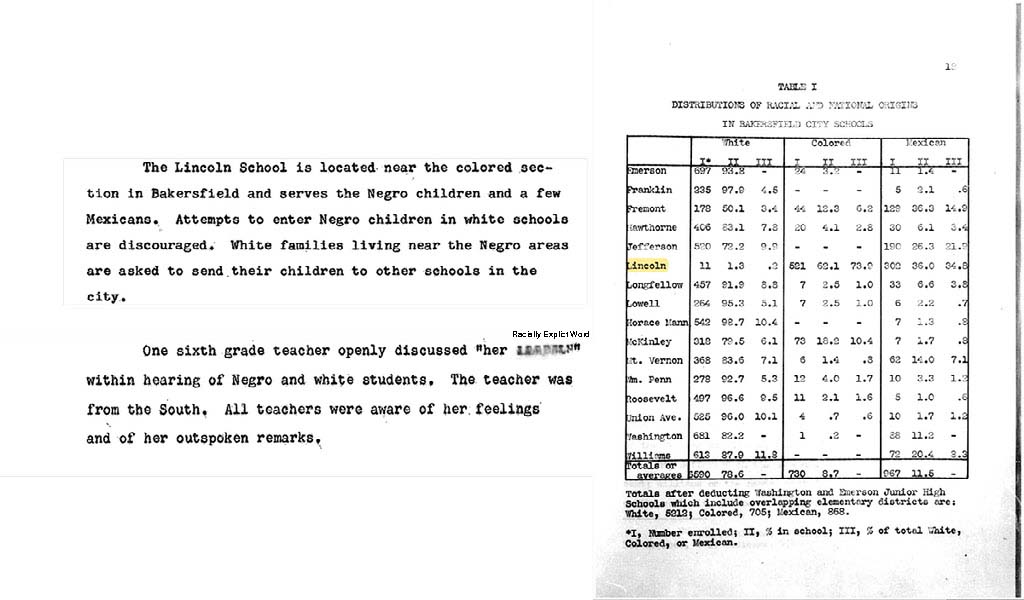

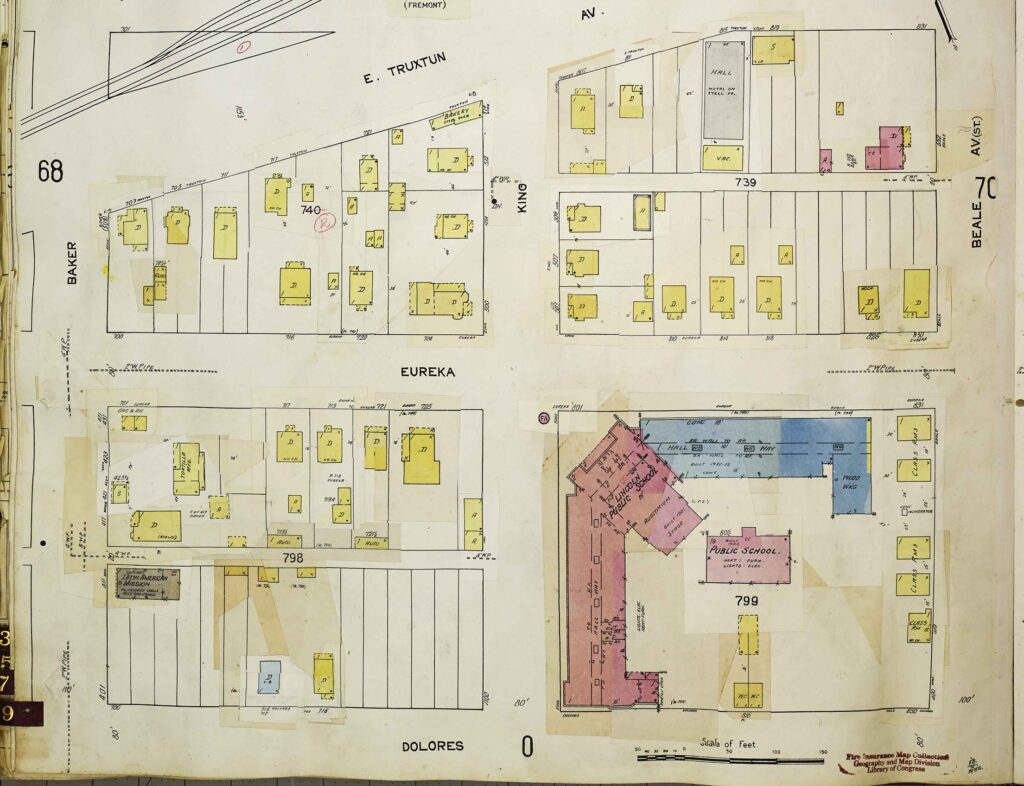

In the 1950s, George Perkins reported in his Master’s thesis, “Survey of Racial Attitudes in Three Communities Kern County California,” that Bakersfield had seen an increase in the Black population. Perkins reported percentages of 5.5 in 1940 and as high as 18.8 in 1948. Mexican residents remained in an average of 14, and as high as 19.9 from 1940 to 1951. Bakersfield of the 1950s remained a majority white city, demographic ranging from 67.1 percent to as high as 83.6 percent in the 10 year period, 1940 to 1951. The Lincoln School was the segregated, Black and Hispanic school.

George Perkins “Survey of Racial Attitudes in Three Communities Kern County California,” Master’s Thesis, University of Montana, 1952.

In 1946, John Randle King found that the Mexican population was treated as an “isolated and transient minority,” reporting that the white population believed that those of Mexican ancestry preferred to live in segregation. King researched bias and racial attitudes from Bakersfield’s white majority and did mention the effects of systemic housing segregation. King states, “One of the most common means by which a majority group can segregate an undesired minority is to restrict its areas of residence. These restrictions may be made by local ordinances, but more common are organized social pressures and restrictive covenants.”

John Randle King, “An inquiry into the status of Mexican Segregation in Metropolitan Bakersfield,” Master’s Thesis, Claremont Graduate School, 1946

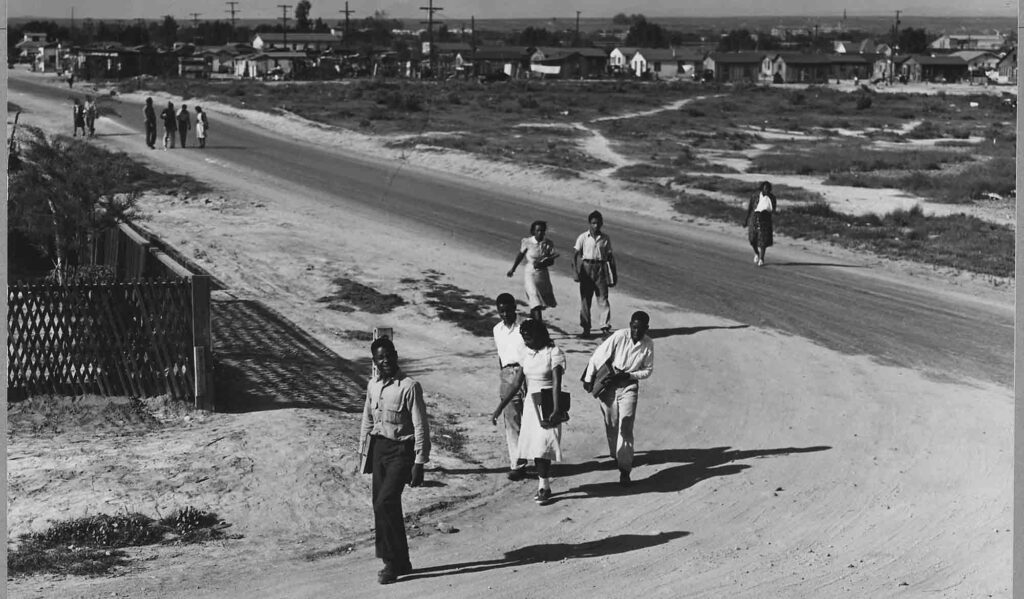

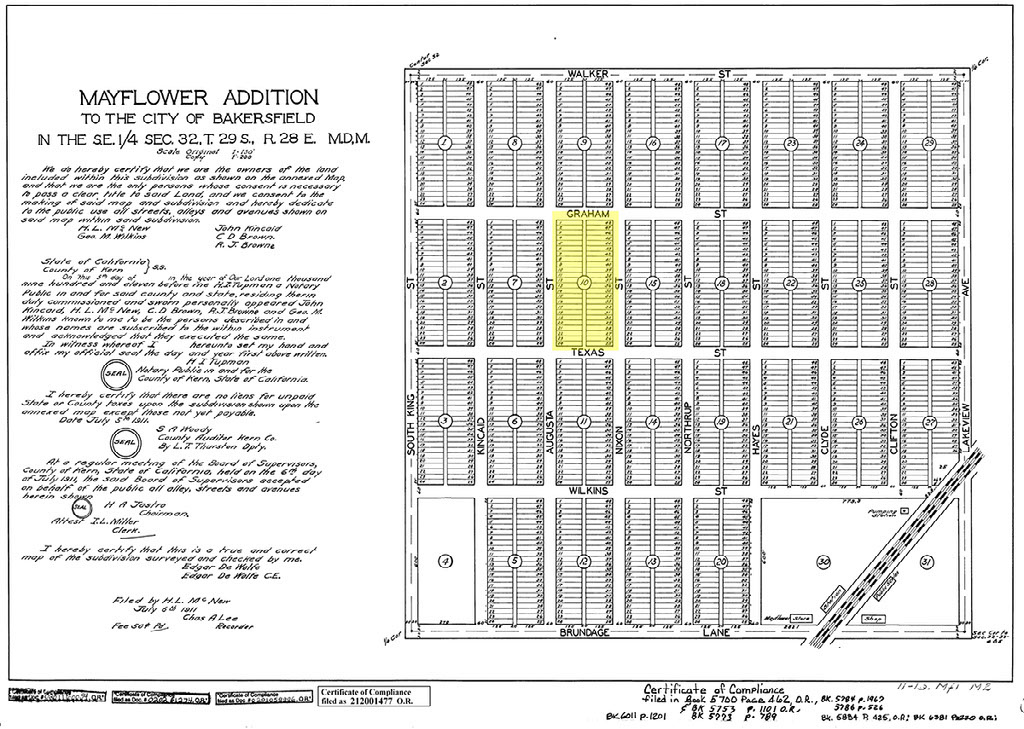

Sunset-Mayflower District- Children of the Mayflower-Sunset tract attended the Lincoln School

The Sunset-Mayflower District was home to much of the city’s poor migrant populations who worked in nearby agricultural fields and labor camps. Due to the black population’s wariness of cohabitating with whites within labor camps, many chose to live with family members who had settled prior or settled in areas where the white population was minimal – like the Sunset-Mayflower District.

While the district’s population was largely impoverished, the racial and ethnic background of the area was rather diverse, housing white, black, Hispanic, and Asian families. Census data from the 1920s, 30s, and 40s show a significant increase in the black population, specifically residing in the Sunset-Mayflower District and a decrease in white residents in the area. This phenomenon is known as “White Flight,” in which white families choose to leave impoverished areas when black and brown families began moving into their communities. Those who migrated out of the Mayflower into newer subdivisions opened up opportunities for housing for blacks to become available. The Sunset Tract and Mayflower Addition were a few of the only tracts in the greater Bakersfield Area that allowed unrestricted buying power to blacks.

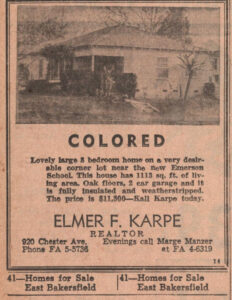

“Early in the decade of the 1940’s, the Elmer F. Karpe Agency was the first realtor to build new homes in the Sunset Mayflower community for sale to non-White buyers… The historic housing movement by the Karpe Agency generated an exodus by white residents of the area.” Parker, Johnie Mae, How Long, Not Long. (Bakersfield, California) 1987

This newspaper ad is an example of racial segregation in Bakersfield housing during the 1950s. It is important to note that the advertisement still used “Colored” in 1956, eight years after Shelley v. Kaemer outlawed the use of racially restrictive covenants. The Press Volume III, No.14, 16 February 1956, 1956-02-16bp. Kern County Newspaper Collection, 2020-002. p11. California State University, Bakersfield, Walter W. Stiern Library-Historical Research Center. http://archives.csub.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/5157

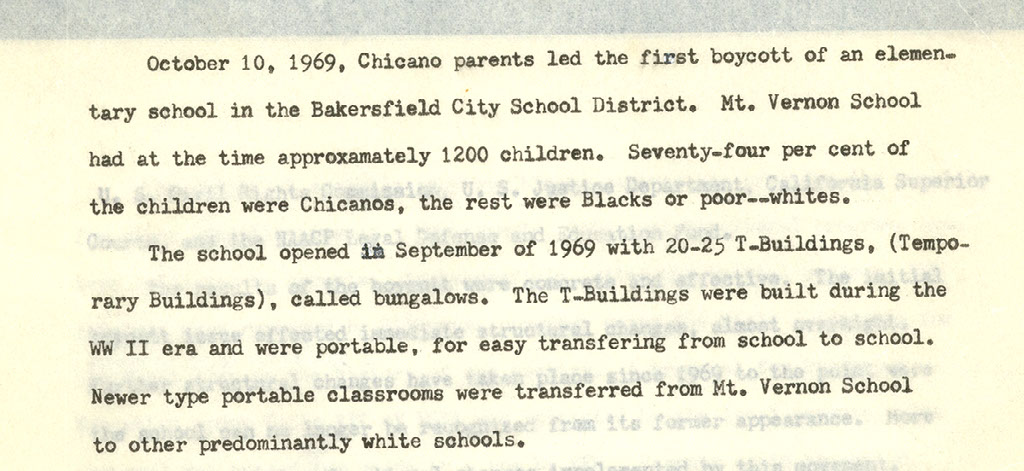

1969- Jesse Alcal, Narrative of the Bakersfield’s School Segregation

In the case of the Bakersfield City School District (BCSD), the State of California and the Office of Civil Rights (Department of Health, Education, and Welfare) agreed and the the federal government followed soon thereafter with a charge that the BCSD was in violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and demanded the district take immediate steps to integrate its white, black, and Mexican American students. The Office of Civil Rights focused on three areas where the BCSD was in violation: 1) “inferior educational services to the district’s minority children…that disadvantage, on the basis of race and ethnicity, [their] educational development”; 2) “creation and maintenance of racially identifiable special education classes” where minority students tended to be over-represented; and 3) maintenance of some schools as racially identifiable by means of zone changes, grade manipulations, and school site selection.” A supplement to the trial brief filed in the case, People of the State of California v Bakersfield City School District, noted that the city’s “schools are racially imbalanced, separate, and isolated” and “that demands have been made to eliminate and alleviate racial imbalance, separation, and isolation” but the “respondent [school board] has failed to exert that effort.”

Jesse Alcala, Oral History with Oliver Rosales. Jesse Alcala Digital Collection, 2020-01-23. California State University, Bakersfield, Walter W. Stiern Library-Historical Research Center. https://archives.csub.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/8956 Accessed March 04, 2024.

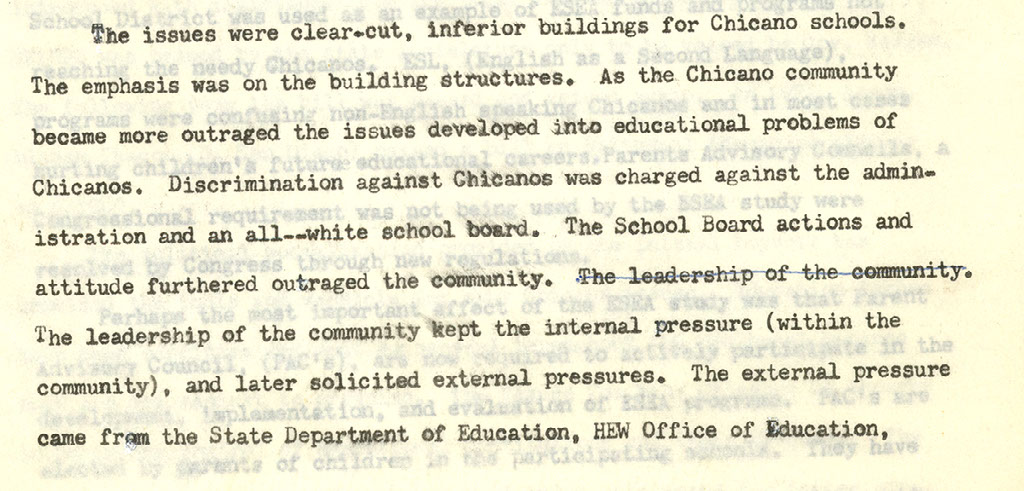

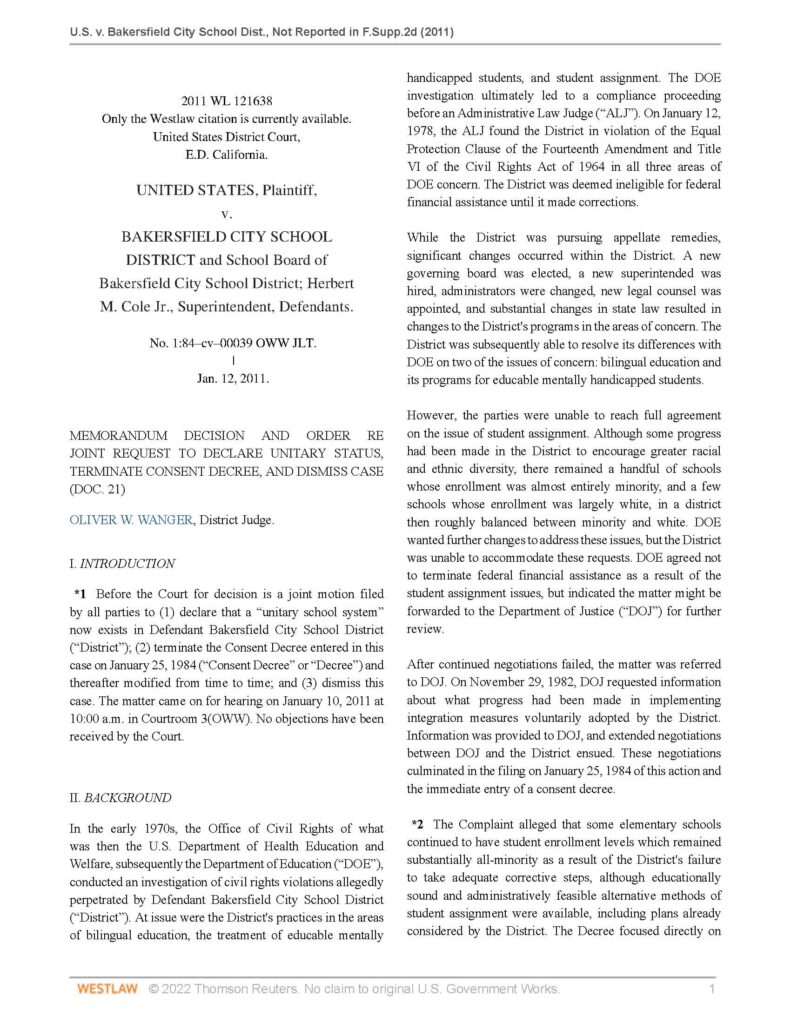

1984- Desegregation, 30 years after Brown v. Board of Education

In 1975, the U.S. government said BCSD was purposely busing students to keep white and black schools separate, a violation of the Civil Rights Act. The ensuing legal battle lasted nearly a decade until in 1984, the U.S. Department of Justice stepped in and sued the district for having “racially imbalanced schools” and to reduce segregation.

The desegregation order was lifted in 2011.

Historic desegregation order against BCSD schools lifted

“A more than 30-year court fight to bring racial equality to Bakersfield City School District campuses is officially over. As a result of the federal case, BCSD schools are more diverse, have bilingual and magnet programs at what now are some of the county’s highest-achieving campuses and educate all students equally, officials said.”

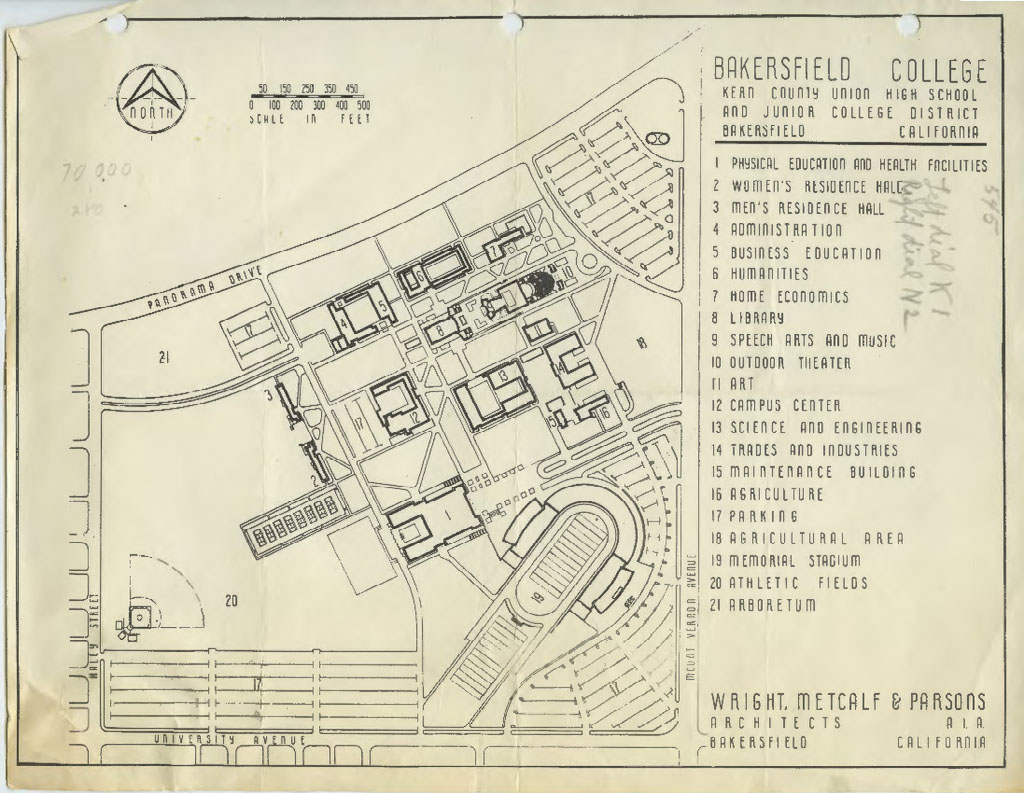

Establishing CSU, Bakersfield

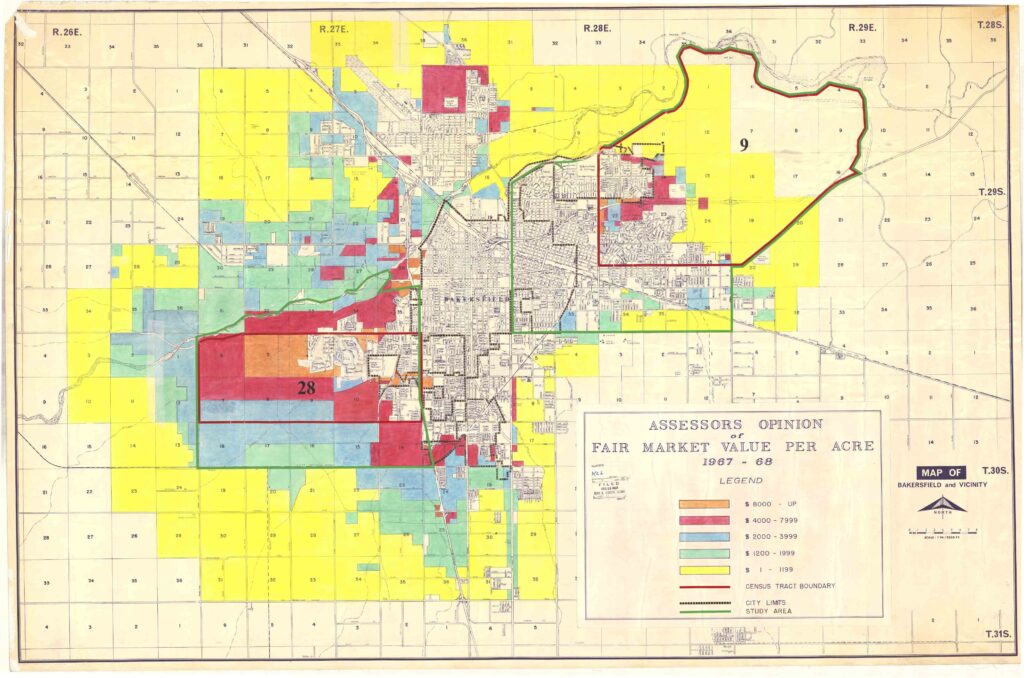

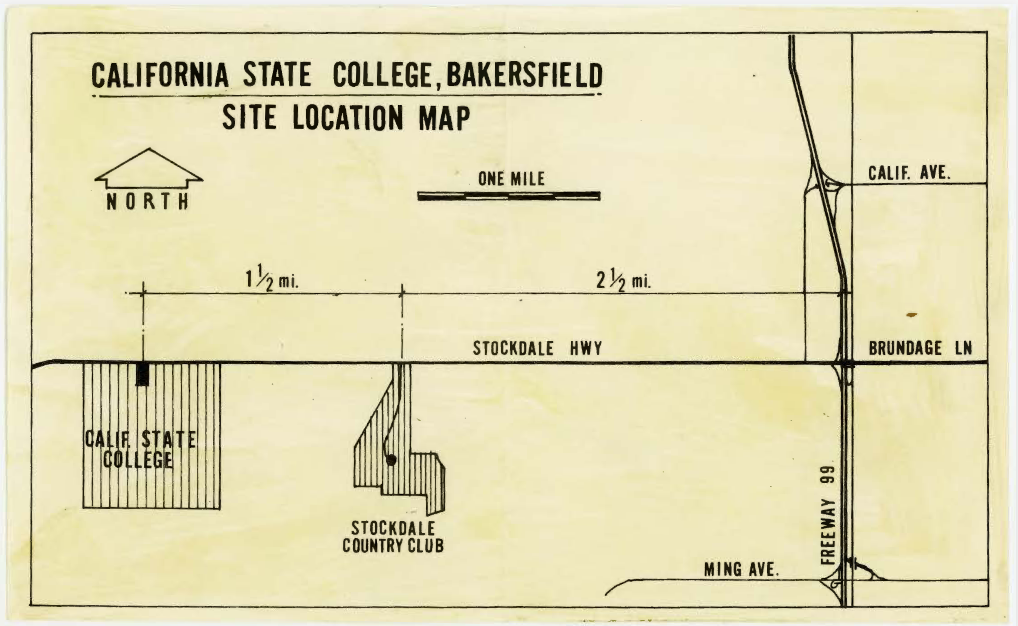

The Stockdale location was the only site to offer adjacent housing and development support. The maps presented to building the site had listed churches, industrial districts, a high school, and new housing by the Stockdale Development Corporation. Kern County Assessor’s Map 1967 CSUB’s future site is at the highest value (Orange).

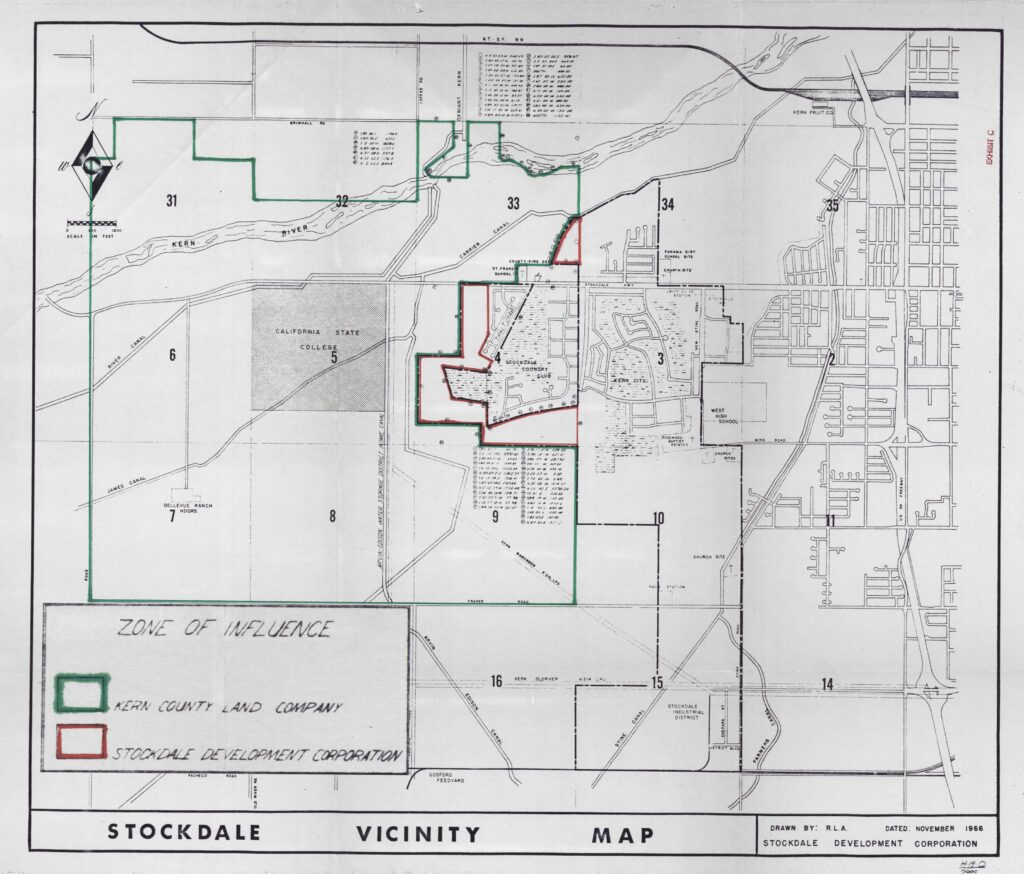

Zone of Influence and Suburban Ideal

Stockdale County Club served as the “Zone of Influence” for the establishment of California State College, Bakersfield. Along with the establishment plan to establish the college, housing had to support the vision of the then California State College, Bakersfield.

On the April 4, 1969, the day of the ground breaking ceremony of California State College, Bakersfield, the Members of the Advisory Board held the reception at Stockdale Country Club, east of the university. The country club is in close proximity, and in recent times, Seven Oaks Country Club was established on the west side of the university.