Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – Covenant Database – East Bakersfield

Education – Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods

Public Housing – Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

Black migrants encountered White, Mexican, Asian, indigenous, and European immigrant settlers and farmers when coming west. The West had limited diversity when it came to black settlers. The West had been largely defined by the area’s powerful white growers. Black migrants left the Jim Crow South only to find similar instances of racism and discrimination that had already limited other racial minorities in the American West.

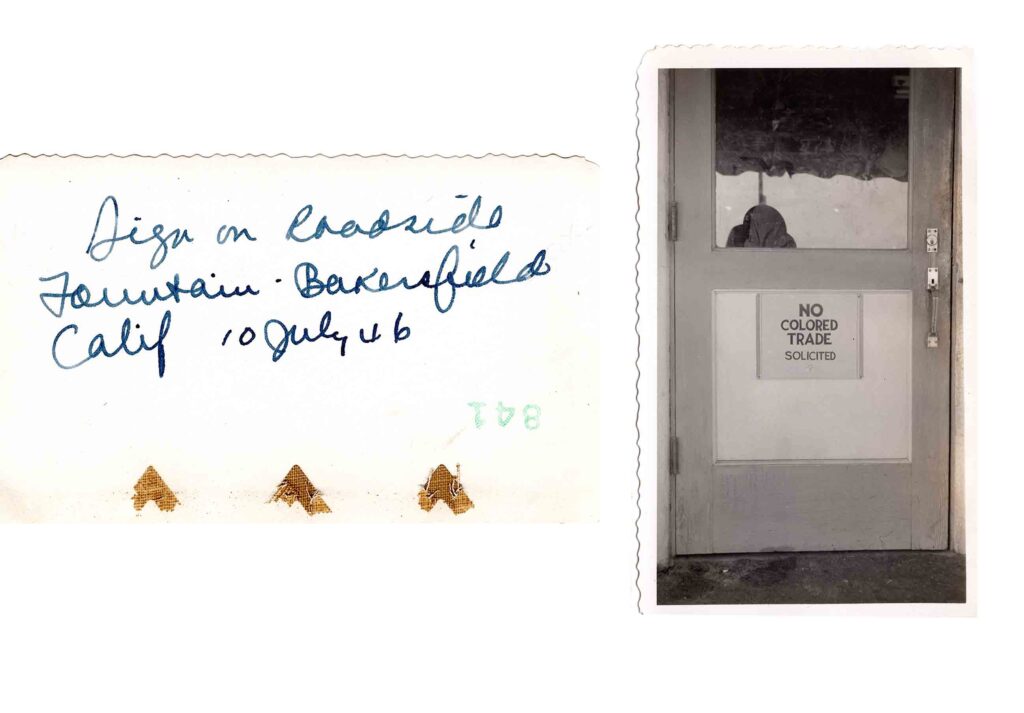

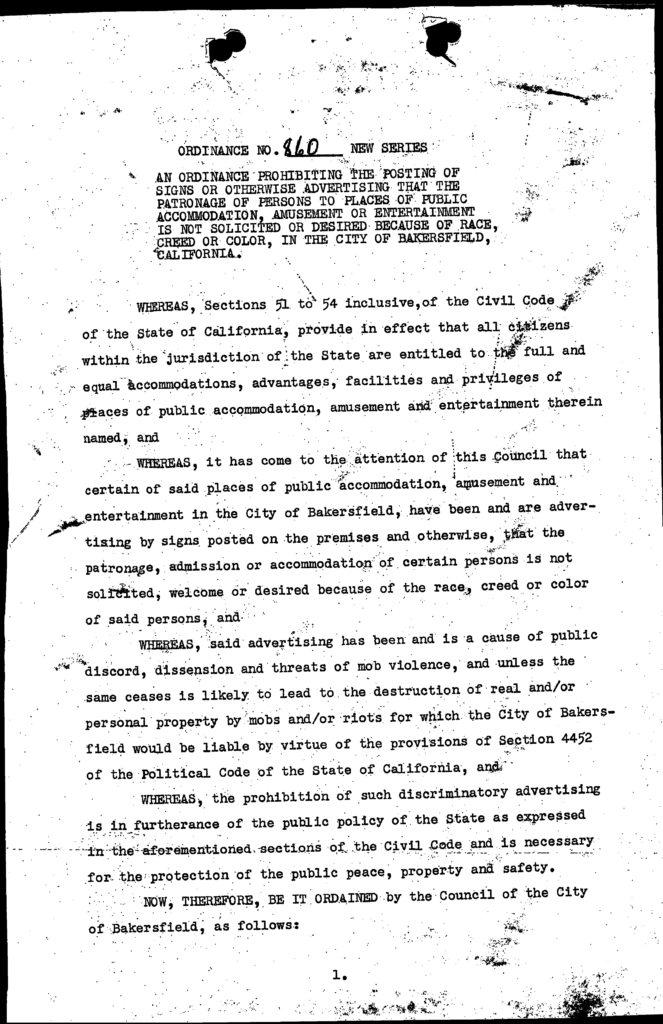

Migrants who came to Buttonwillow found the “Jim Crow North,” as Robert Williams, a local resident said. Williams thought he had left discrimination in the south, only to find a “No Colored Trade” sign posted on a Buttonwillow café. Black migrants resisted and fought for change. Williams told historian Peter La Chappelle, who interviewed him in 1997, that he confronted the owner (a friend of Williams) and told him that he would not come in out of protest, even if the owner did not mean the sign to include Williams. This was not unique to the 1930s, as the Ku Klux Klan had already been active in the early 1920s in Taft, a known “sundown town.” In 1922, the New York Times reported on the case against the Kern KKK: “In its first report since it began inquiring into the recent activities of the masked night riders in the Central Valley oil fields, the Kern County Grand Jury delivered a presentment against the Ku Klux Klan today.” Other forms of disenfranchisement and discrimination included anti-miscegenation laws, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and housing discrimination.

Peter La Chappelle, “‘Shadows of the Dust’ The Expectation and Ordeal of California’s African-American Dust Bowl Migrants Southern San Joaquin Valley, 1929-1941,” (MA Thesis, CSU Bakersfield 1997) https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/concern/theses/r494vr48j

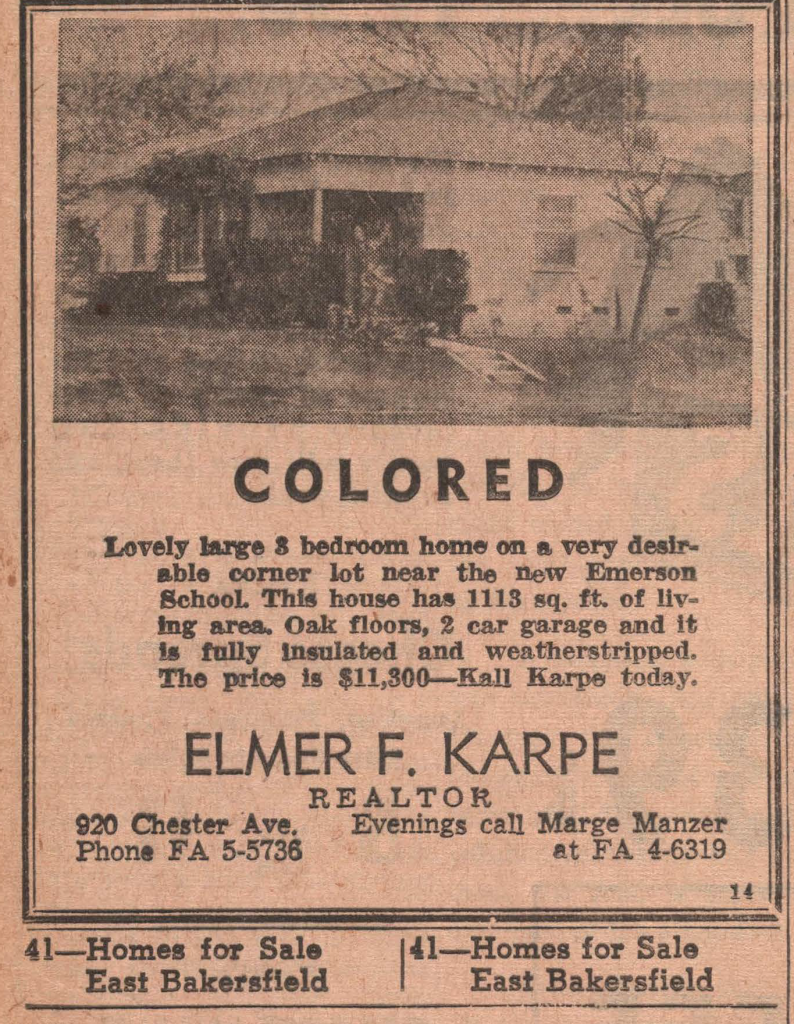

Housing discrimination included responses to deny housing. Johnie Mae Parker, an activist and historian, recounted, in her book How Long? Not Long!, that “In approaching a number of houses which had ‘For Sale or Rent’ signs posted, the response was, ‘Sorry, we don’t sell or rent to Colored.’ Two of such houses happened to be located on Kincaid Street in the Mayflower community. One of the houses was for sale by owner, the other one was for sale by realtor.”

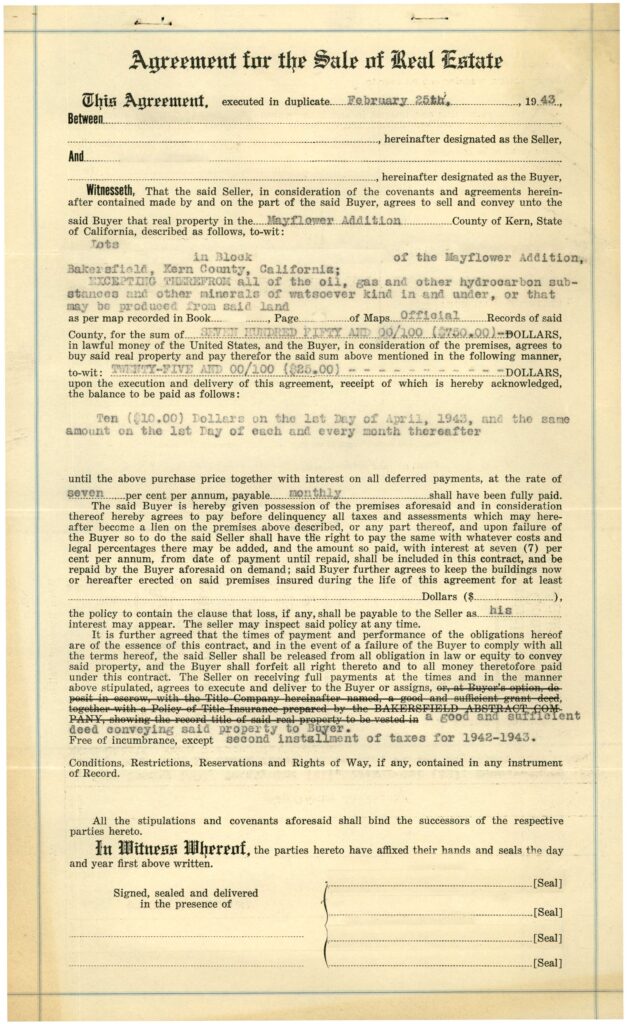

With FHA (Federal Housing Administration) and HOLC (Homeowners Loan Corporation) loans out of reach, “buying on contract” was the process of “renting to own.” Minority home buyers were baited with the dream of homeownership, with the loans offered by real estate agents. The reality instead resulted in attempting to purchase homes under the agreement and conditions of a real estate broker. The broker owned and loaned the property to prospective buyers who did not have access to bank loans. The process of buying from the broker and owner created loans access with no protections or liability. Since FHA and HOLC loans did not operate in neighborhoods with poverty and areas where inadequate municipal services, “buying on contract” became the purchase method for many minorities well after the postwar period.