Before 1938 – Buying on Contract – Covenants – Covenant Database – East Bakersfield

Education – Eminent Domain – Moving into a Neighborhood – Neighborhoods

Public Housing – Resources – Rumford Fair Housing Act – Suburban Expansion – Zoning

Older minority neighborhoods often received less urban investment than suburban and new housing. Destruction or purchasing under eminent domain, was a common way for cities to build in area they saw their least investment. Chavez Ravine, the well known case of Dodger Stadium, was initially purchased under eminent domain to build public housing but never became housing. Instead, the Los Angeles City Council used the acquired space to build Dodger Stadium (LAPL Photographs).

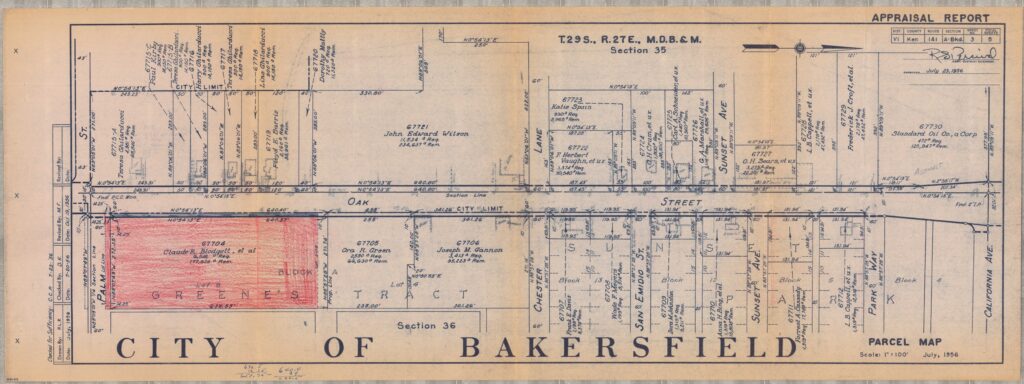

Minority communities in cities lacked equal investment, and rather than supporting the reconstruction of dilapidated neighborhoods, or urban investment, homes were purchased under eminent domain for public projects, and highway initiatives, in order to condemn of dilapidated and aging homes. Like the case of many cities and counties, eminent domain reclassifications allowed city governments and federally funded programs to acquire homes, destroy, and at times for the promise to build public housing, without adequate or equal replacement. The City used eminent domain to acquire properties but instead invested in urban development for tourism and industry.

Excerpt from an oral history with Christina McClanahan detailing how the building of the State Route 58 affected her.

“The reason I thought about that is when we were looking at this house. When we lived up on Madison Street and the state bought our house for the freeway and we thought we’d just go out. It was 1960 by then, we thought we’d just go out and by a house. I went out and there just wasn’t a house for me… I think my husband must have mentioned something at the time we could sue. So his boss called him in and told him that he could not sue, if he did he wouldn’t have a job.”

Christina McClanahan, 1981 California Odyssey Project, Full Interview

| McClanahan, Christina Veola Williams (133) | McClanahan was born in Boley, Okfuskee County, Oklahoma in 1929. This interview provides an African American perspective to the Dust Bowl. She and her family came to Rosedale, California in 1936. McClanahan considers discrimination toward African Americans, the home remedies her family used for illness, her father’s involvement in WPA and SRA, discrepancies with a social worker and obtaining welfare, how labor contractors cheated anyone they could, and why African Americans saw Roosevelt as a great president. |

Other Dustbowl Interviews https://hrc.csub.edu/odyssey/dbinterviews/

African American Voices https://hrc.csub.edu/african-american-voices/oral-history/

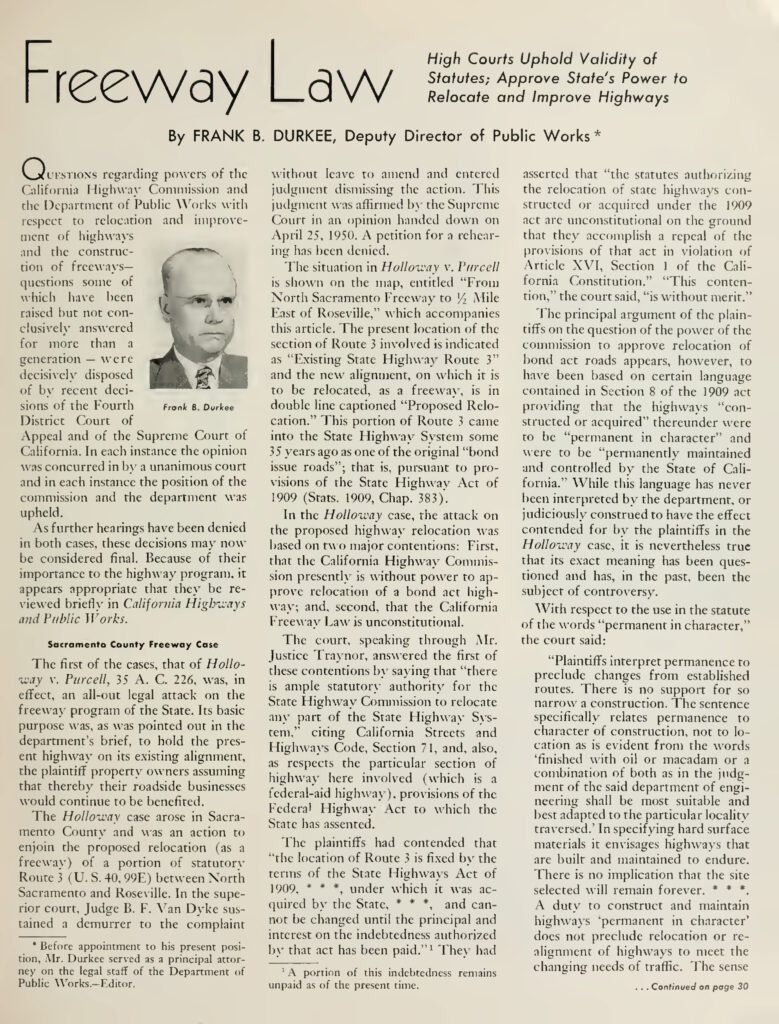

In 1950, lawsuits tested the “Freeway Law” of 1939, which allowed the state to buy land and create ” …’expressway,’ such as divided roadway, separated crosstraffic, no left turns, direct interchange facility, ample right of way, no pedestrians, simple and adequate signs, are a definite requirement, but the important fundamental quality that creates the high, lasting character is the ‘freeway principle.'” Fred J. Grumm, “Freeways: Progress Toward the Ultimate in Highway Transportation,” California Highway and Public Works, March-April 1950, Vol 3-4, p55

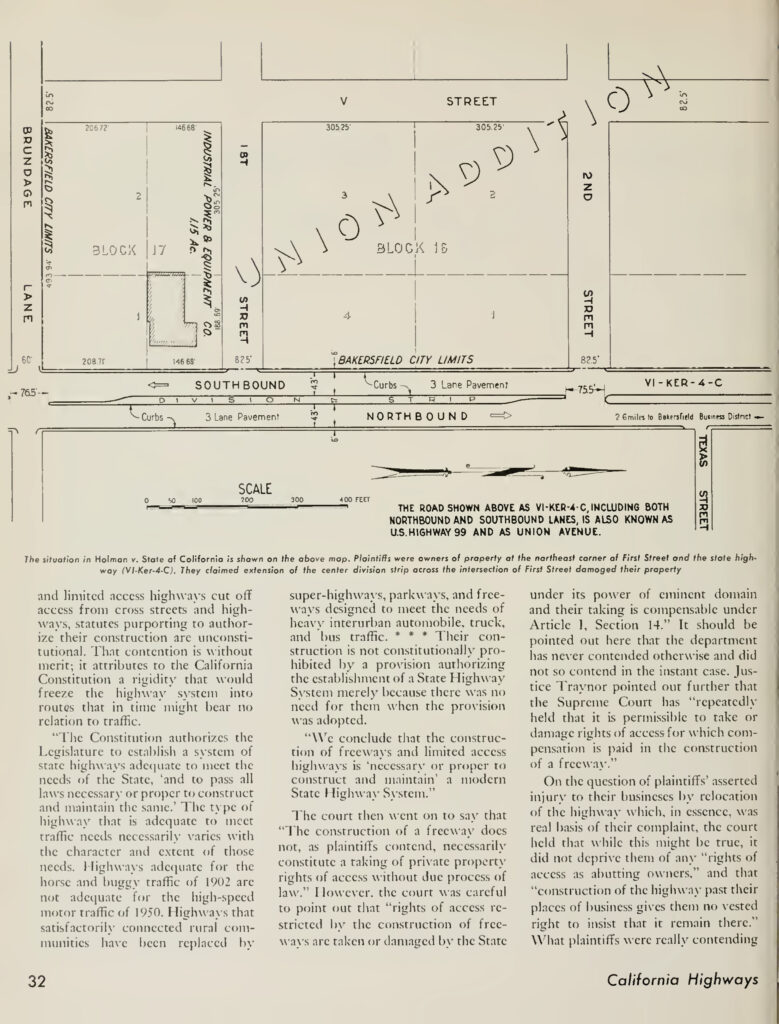

The high courts upheld and denied the challenges to the 1939 Freeway Law. The challenges originated from Sacramento and Bakersfield.

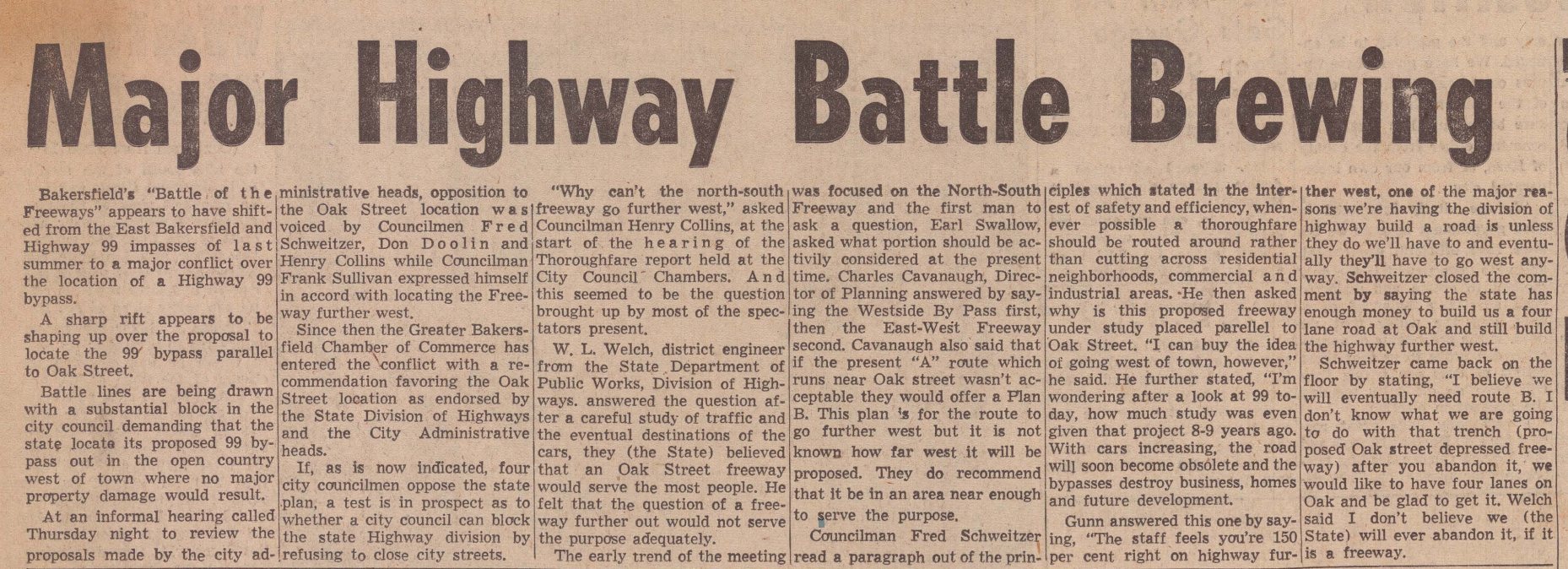

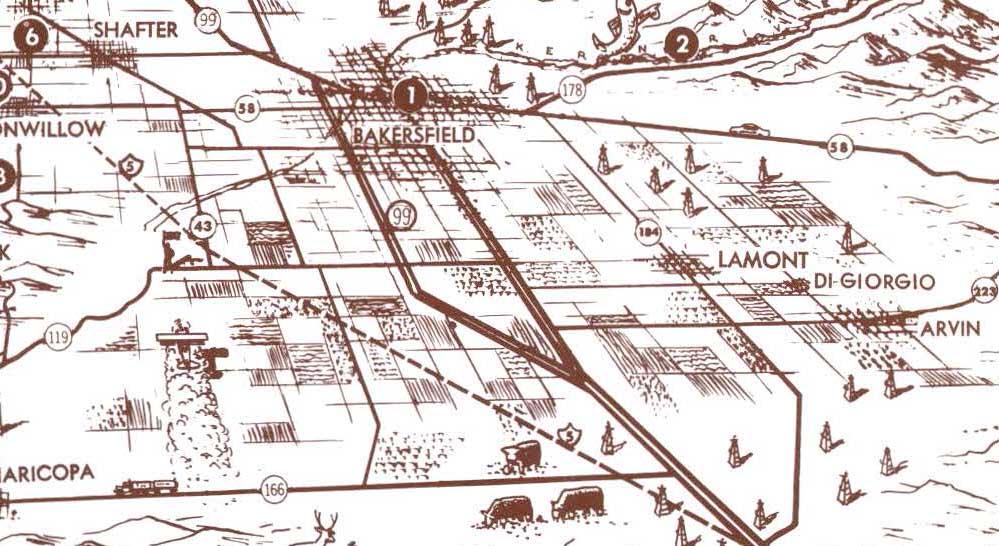

The building of the freeway was not free or without resistance in Bakersfield. Residents protested the highway that was going to be placed parallel to Oak St, they wanted to avoid property destruction. Councilman Henry Collins suggested moving the 99 further west. Some of the Oak Street and Highway 99 will be the future site of the Centennial Corridor 57 years later.

The Press Volume III, No. 11, 05 February 1956. Kern County Newspaper Collection, 2020-002. California State University, Bakersfield, Walter W. Stiern Library-Historical Research Center. https://archives.csub.edu/repositories/3/archival_objects/6875 Accessed April 26, 2023.

Section of Oak St. 10 years before the highway, July 1956.

“Oak Street, before Highway 99,” Claude Blodget Collection, 1956

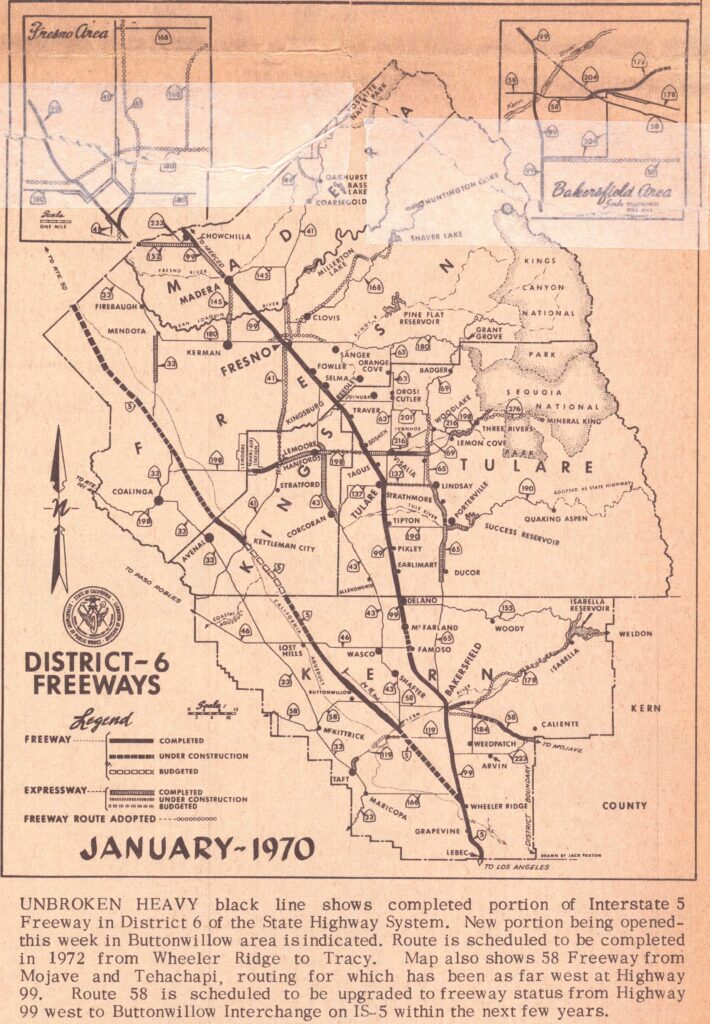

“Construction of the Interstate 5 in Kern County started in May, 1965. Approximately 75 miles of Interstate 5 will be build in Kern County from Wheeler Ridge to the Kings County Line. the Kern portion of the Interstate 5 is expected to be completed by 1972.” “BW Caravan Will Initiate Freeway,” Buttonwillow Times, February 5, 1970, p1

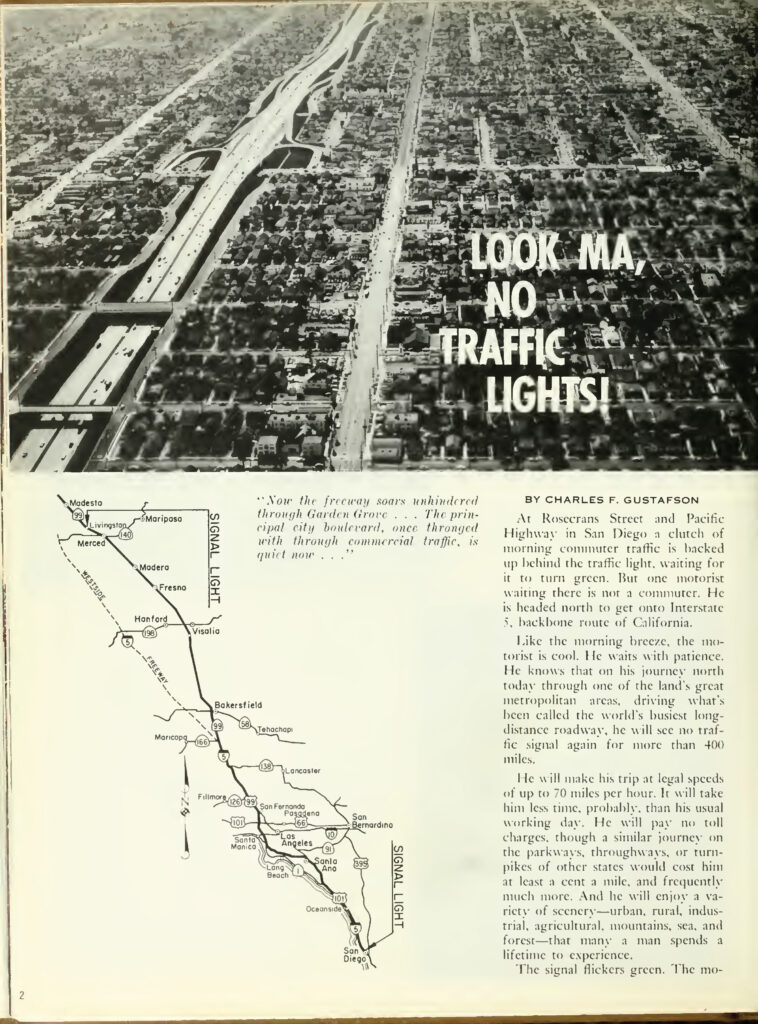

In 1966, the California Highway and Public Works magazine lauded the completion of the Interstate 5 and Highway 99 with no stop signs or lights. Previously, the old highway systems intersected city streets. In Bakersfield, Highway 99 ran through Union Avenue. After the completion, the highway was moved to run stop free parallel to Oak/Wible street. State Route 58 was completed to end at the Brundage and Oak Intersection. Previously State Route 466 was completed through Tehachapi, ending near Bakersfield, and later a freeway was constructed to run parallel to Brundage Lane. The 466 would run to the 99, making it State Signal Route 58. By 1966, the highway system would be complete, lauding, “Look Ma, No Lights!”

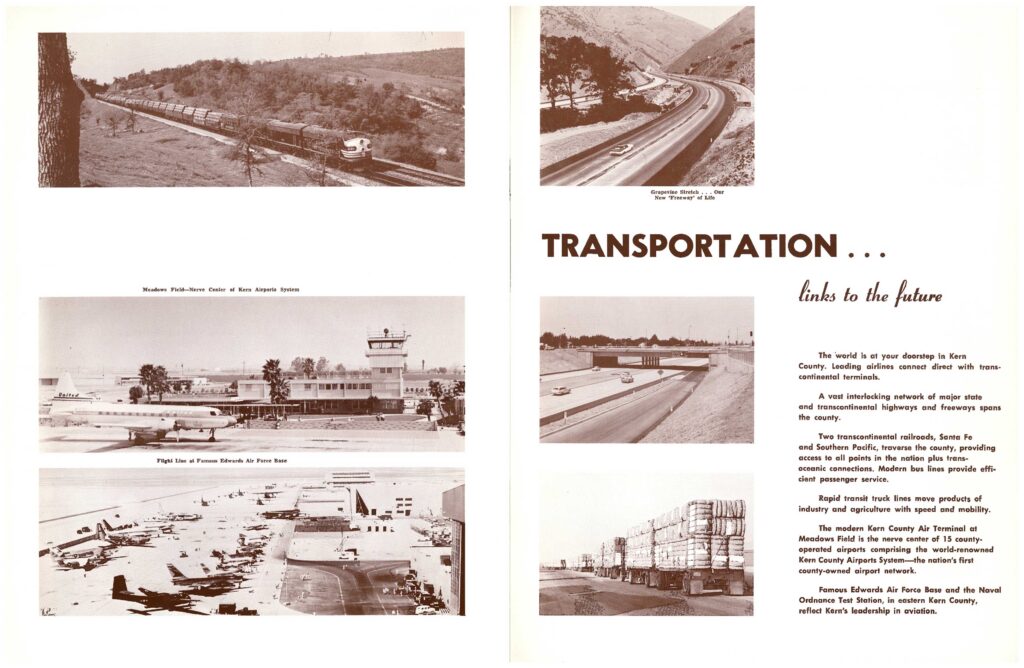

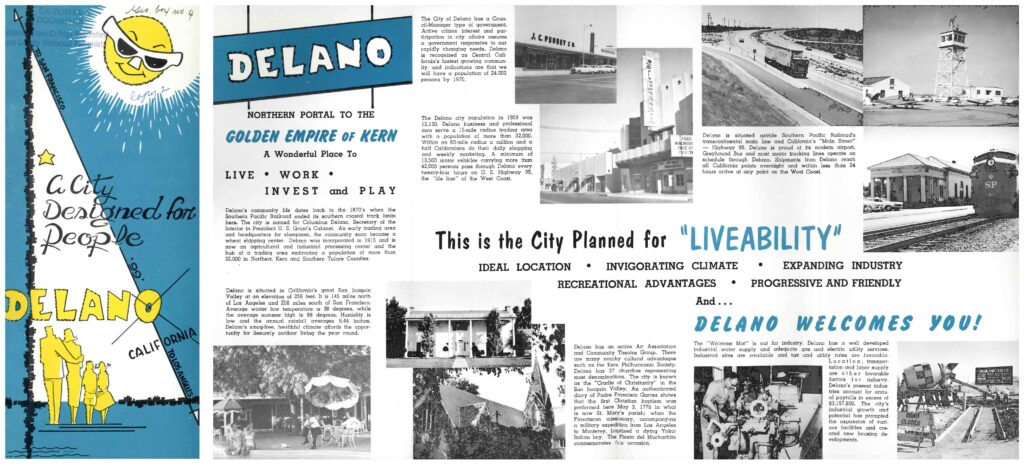

After the 1952 earthquake, the County of Kern invested millions in centering Kern County as a destination for commerce, investment, and tourism. Lake Isabella (Kern River Valley), Lake Ming (Bakersfield) and Lake Woollomes (Delano) were created as recreational and boating lakes in the late 1950s, following post-earthquake investment. By the 1960s, Kern cities and townships had re-envisioned themselves as new areas of commerce, housing, and recreation. The 1960s California highway era brought continued investment and centering cities around highway access and easy stops on the way to large cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco.

The highway became a center of economic commerce. This 1960s advertisement centers Delano on top of a map with a clear intersection of highway “99” with northern access to San Francisco and Los Angeles. The highway becomes a modern predictor of financial investment.

Most recently, starting in 2014-Present, the City of Bakersfield and the County of Kern moved forward with the Centennial Corridor Project, and displacing an estimated 300 homes, and over 900 residents. U.S. EPA DETAILED COMMENTS ON THE DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT FOR THE CENTENNIAL CORRIDOR PROJECT, KERN COUNTY, CALIFORNIA, JULY 8, 2014

Bakersfield Opens New Centennial Corridor Freeway

The two-mile freeway demolished a swath of the Westpark neighborhood: 271 homes, 15 multi-family buildings and 36 commercial structures